"The

clergyacademics, representatives of the ideology ofmediaeval feudalismcapitalism, felt the influence of the historic transformation no less acutely. The invention of theart of printinginternet, and the requirements of extended commerce, robbedthe clergyacademia not only of its monopoly ofreading and writing, but also of that ofhigher education but also that of authority. Division of labour was being introduced also into the realm of intellectual work. The newly arising class ofjuristsbloggers and podcasters (?) drovethe clergyacademics out of a series of very influential positions.The clergyAcademia was also beginning to become largely superfluous, and it acknowledged this fact by growing lazier and more ignorant. The more superfluous it became, the more it grew in numbers, thanks to the enormous riches which it still kept on augmenting by fair means or foul."Friedrich Engels, The Peasant War in Germany1

It seems no accident that the Reformation was to have begun Wittenberg, a town whose main business was the university. And we do seem to be on the precipice of a new age, a new form of intellectual organisation. With what is going on in universities, it can't seem to come quickly enough. And yet there are few real remunerative prospects for serious scholars under platform capitalism. I don't know what is to come, and it is deeply troubling. The smartest and most generous teachers and thinkers I know are being crushed by this system, while the bullies, idiots and hypocrites are continuously promoted. Toward the end of my PhD, I made the mistake to look further into what artists were doing around the German Peasant War of 1525 and what became of those who took the side of the peasantry. This is not going to be a happy tale…

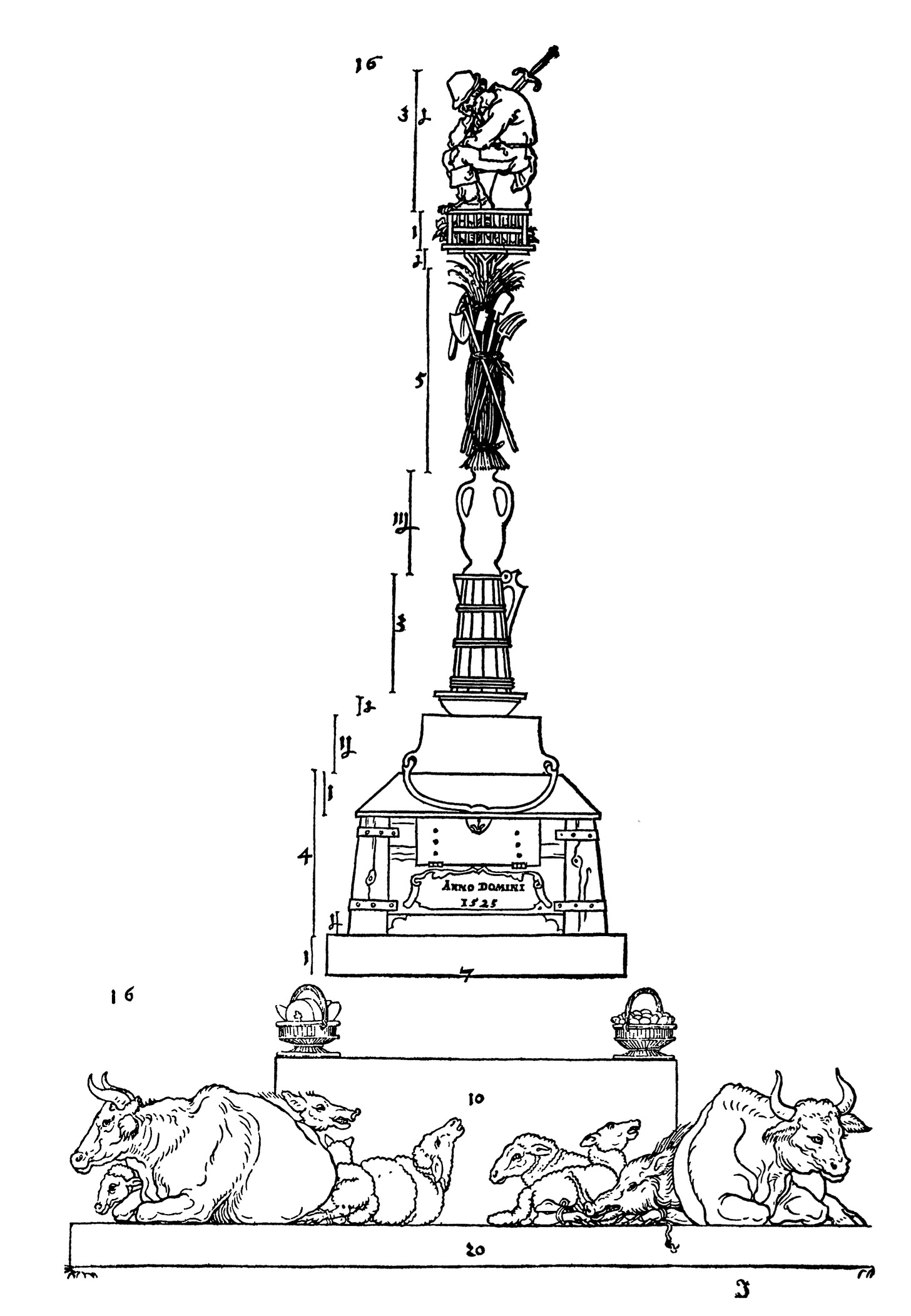

As history is never truly about the past, but written anew with each new age, interpretations will tend to shift, and in the last twenty years or so, particularly, seem to end in some pretty uncomfortable contortions under an ideology so overarching as to claim to be otherwise, namely neoliberalism.2 To search the internet, it would seem that it is quite uncertain as to whether famed artist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer, was a great champion of the peasants, and as such, critical of Martin Luther’s position, or remained loyal to Luther. (Dürer was actually responsible for a number of engravings essentially mocking the boorishness of the peasantry, which are sometimes, I think unconvincingly, recast as a subversion.) Interestingly it is often in pointing to his Unterweisung der Messung (Treatise on Measurement), of 1525, that the argument is made for his sympathy with the peasantry.3 The inclusion, in this Treatise, of a monument to the vanquished peasants, featuring all the accoutrements of the peasantry, topped with a peasant with a sword through his back, is the suggested as the evidence for this (as opposed to quite a horrific example to the contrary).

Albrecht Dürer, sketch for a monument to the vanquished peasants in Unterweisung der Messung (Treatise on Measurement), 1525

Art Historian Erwin Panofsky, however, claims that “Dürer never wavered for a moment in his loyalty to Luther”4 such that the monument was indeed intended to (witlessly) mock the peasants. This assertion is made more plausible upon considering his earlier work the “Treatise on Fortification” which Panofsky suggests was: “possibly connected with one of the earliest “slum-clearing projects” in history, the Augsburg “Fuggerei” of I5I9/2.”5 Said Fuggerei was of course the work of one Jakob “the rich” Fugger, who is said to have paid minimal taxes but introduced this philanthropic enterprise for the sake of those poor people he deemed worthy. Dürer was a friend of the Fuggers, and apparently quite horrified by the hoardes of peasants in revolt, ultimately leading to his design of fortifictions for the city of Nuremberg, which were executed some ten years after his death.6

Panofsky’s reference to the Fuggerei as a “slum-clearing project” is the only one I can find via searches on Google, Google Scholar, Duck Duck Go (my preferred search engine), and through the University of Sydney Library website, all of which present me solely with puff pieces about the world’s oldest social housing project. The Fugger family are wealthy even to this day. Though, through the library, there are articles that manage to critique its obvious paternalism (those lucky enough to be lifted above immiseration through the reduced rent were subject to regulations as to exactly to what kind of life they could live):

“Since the late Middle Ages, the city administrations began to distinguish between “decent” and “dishonest” paupers, provoked by a rising number of impoverished people within the cities. Only the “decent” paupers were deemed worthy of public support, which was generally carried out by religious or private foundations supported by wealthier citizens. The Fuggerei was not the only charitable institution within the city walls, but it was special through it sheer size—it boasted more than one hundred housing units, but lacked a communal center or public rooms, the reason being that this was the disciplinary character of the social sub-city which was surrounded by its own walls. The residents were supposed to enjoy neither gregarious meetings nor festivities nor idleness. They were rather supposed to lead a God-fearing and industrious life. The doors of the district were closed during the night, shutting out everybody who had left the taverns too late that evening.”7

We will remember that Jakob Fugger was essentially richer than Elon Musk, and paid a flat rate to the tax authorities that they would not disclose his income. So around 100 dwellings were his contribution to the poor, whom his actions, in many ways, had directly immiserated. Dürer is said to have been particularly interested in raising the living conditions of artisans, but nevertheless came firmly down on the side of the new order, designing gated communities in all their paternalistic glory. He may as well have been a “public artist” of today, with the already anticipated increase in property values these great works of genius would seem to entail. And of the artists surrounding the German Renaissance, the most famous names are of course that of Cranach and Dürer, such that one might be warned of taking up the cause of the disenfranchised both in terms of immediate prospects and that of one’s legacy. The pleasantries of Renaissance Protestant art with their assertions of everyday morality are perfectly aligned with the art of the Neoliberal era, in being produced to extol a similar form of virtue through remaining blind to the plight of the oppressed, something which almost characterises the art of the establishment in Sydney today. The rather more vital Late Gothic art preceding the Peasant War was to slip out of favour, and while Cranach was occassionally a good painter and Dürer's technical prowess little in doubt, other artists of the time have ultimately passed out of the collective memory seemingly not for a lack of merit but rather their political views. The sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider (1460-1531), for example, was responsible for many incredible carving works on alter pieces such as this one:

Supposed Self Portrait Tilman Riemenschneider in the predella of the Marien altar Creglingen, 1505-1510

During the Peasant War, Riemenschneider, (as a city counsellor) argued for acknowledgement of the plight of the peasants, thereby allying himself with the lower classes against the Prince-Bishop, Conrad von Thüngen. He was, by then, an elderly man who was not involved in the fighting. For this he was tortured. In a particularly horrific and evocative act, he had his hands broken. He was never to receive another commission thereafter (though he commanded a large studio). Still, worse was the demise of painter Jörg Ratgeb, who was responsible for this excellent piece:

Jörg Ratgeb, Herrenberg Altarpiece, 1519

Ratgeb was was elected councillor and chancellor by the peasants, and became part of the military contingent of the revolt, such that he was charged with treason, and was drawn and quartered in 1526.

Matthias Grünewald -- “Pain extinguishes itself”

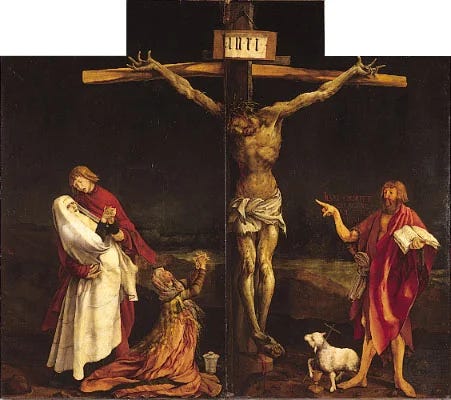

Matthias Grünewald, “Central Panel of the Isenheim Alterpiece,” 1515. (I thoroughly recommend looking at the video of the whole thing, which opens up into several different scenes, it is very excellent.)

With historians still grappling with scholarship written under the DDR, reading about the artists of the peasant war can be quite a weird experience. In “Mit Dem Kreidestift Und Farben: Revolutionizing Grünewald in the German Democratic Republic” Historian Tamara Golan explains that Grünewald scholar W. K. Zülch at some point reframed Matthias Grünewald as a participant in the Peasant War in order to appease the East German establishment.8 Golan is doubtless a far more accomplished scholar than I am, and yet I cannot quite get past the internal contradictions in the article. Golan begins the piece cautioning against ascribing too strict an ideological bent to the artworks produced under the DDR9 and yet seemingly surmises that artists were lead hopelessly towards the stylistic turns of Grünewald simply blindly following the efforts of Zülch. There is some evidence to what the subtext of all of this might be within Golan's ekphrasis of a painting by Heinz Zander:

"The central panel depicts a cluster of militant peasants who erupt from the grounds of history, as it were, overtaking the slumped bodies of armour-clad elites whose corpses pointedly make up the picture’s compositional margins. The violence threatened by these axe-wielding peasants seems poised to encroach into the viewer’s space –not through any feats of illusionism, but through the centrifugal force exerted by the stocky, hypermasculine forms of these revolutionary heroes and the maelstrom of explosive bursts of red and orange that illuminate them. This is the Peasants’ War as a heroic revolution from below, rendered with Grünewald’s volatile palette and frenzied lines."10

One may well ask what a peasant war is if not a heroic revolution from below? An attack on the god-given property rights of the elites by these dirty "hypermasculine" figures?

Also by Golan's reckoning, and even with the limited available information regarding Grünewald, it had already long been believed that his untimely demise in poverty, precipitated by leaving his commission at Isenheim in a hurry (suggesting he was not fully paid), was likely due to a disagreement over current events, i.e. The Peasant War. This was, at very least, believed enough before Zülch's efforts to have been the subject of Paul Hindemith's 1938 Opera Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter) (which was banned by the Nazis), which details Grünewald's struggle for expression within the confines of an oppressive regime and his flight to join the peasant struggle (bizarrely the Nazis also attempted to co-opt Grünewald to their own cause).11

For my part, I find the apparently vexed question of Grünewald's active or passive participation in the rebellion largely irrelevant. I am convinced by Golan's argument that Zülch overstated the revolutionary fervour of Grünewald towards his own ends, but even in Golan’s reckoning, in the same magazine that published one of Zülch's most famous essays "two articles appear each on Dürer, Cranach, and the German Renaissance broadly,"12 such that the particular affiliations of these artists do not seem to have been hugely important. Both Karl Marx and Engels praised artists of the Renaissance for their revolutionary fervour (Engels wrote about Dürer)13, and would seem to have tended to view the innovation of the art as worthy of being separated from the particular affiliations of the artist (especially in the case of someone like Honoré de Balzac), such that overstating Grünewald's political affiliations seems unnecessary.

Grünewald's “Isenheim Altarpiece” (c. 1509–15), nonetheless has remained a source of inspiration and wonder, being amongst the most dark and horrific depictions of the crucifixion scene ever represented, forming an important backdrop of the excellent post-war German novelist W.G. Sebald’s first novel After Nature and his 1996 novel Emigrants, where it is described (by the fictional painter Max Ferber), thus:

“The extreme vision of that strange man, which was lodged in every detail, distorted every limb, and infected the colours like an illness, was one I had always felt in tune with, and now I found myself feeling confirmed by the direct encounter. The monstrosity of that suffering, which, emanating from the figures depicted, spread to cover the whole of Nature, only to flood back from the lifeless landscape to the humans marked by death, rose and ebbed within me like a tide. Looking at those gashed bodies, and at the witnesses of the execution, doubled up by grief like snapped reads, I gradually understood that, beyond a certain point, black pain blocks out the one thing that is essential to its being experienced – consciousness – and so perhaps extinguishes itself; we know very little about this.”14

Sebald is an incredible writer (first introduced to me by musician Rory Stenning), and there is really something to be said for the ekphrases of novelists in conveying the poetic truth over another shallow rationale. Artists such as myself will tend to find the work of art historians very strange on the point of pathologising, as brushstrokes and colour choices are referred to as somehow revelatory of the interior workings of the soul, as predisposed toward whatever political ends they would serve (none at all by the usual reckoning). But life is more than any of this. The bizarre belief in the “cultural Marxism” of the universities is a persistent nonsense that masks the hyper competitive nature of institutions which favour empty “outputs” over serious scholarship. I tend to favour solid materialist analysis surrounding events and find it especially odd that many art historians seem to argue over liberties being taken with the truth, whilst failing to acknowledge that the materialist approach that we now favour, wherein human beings and other factors converge to create historical events (as opposed to strictly the actions of the great men of history) owes a lot to Marx and Marxist scholarship. In fact, what I think of in reading Sebald's rather more poetic (as opposed to formalist) ekphrasis takes me directly to the times in which Grünewald was working, such that I see no real reason for this scholarship following 19th century appeals to "art for art's sake", since art always exists in the world. The passage that comes to mind reading Sebald is from Engel's The German Peasant War of 1525, which details events leading up to the war including events, for instance a peasant war in Hungary in 1514, and the demise of revolutionary leader György Dózsa, that has haunted my memory since I first read it:

"Dózsa suffered defeat before Szegedin and moved to Czanad which he captured, having defeated an army of the nobility under Batory Istvan and Bishop Esakye, and having perpetrated bloody repressions on the prisoners, among them the Bishop and the royal Chancellor Teleky, for the atrocities committed on the Rakos. In Czanad he proclaimed a republic, abolition of the nobility, general equality and sovereignty of the people, and then moved toward Temesvar, to which place Batory had rushed with his army. But during the siege of this fortress which lasted for two months and while he was being reinforced by a new army under Anton Hosza, his two army columns in Upper Hungary suffered defeat in several battles at the hand of the nobility, and Johann Zapolya, with his Transylvanian army, moved against him. The peasants were attacked by Zapolya and dispersed. Dózsa was captured, roasted on a red hot throne, and his flesh eaten by his own people, whose lives were granted to them only under this condition. The dispersed peasants, reassembled by Lawrence and Hosza, were defeated again, and whoever fell into the hands of the enemies were either impaled or hanged. The peasants’ corpses hung in thousands along the roads or at the entrances of burned-down villages. According to reports, about 60,000 either fell in battle, or were massacred. The nobility took care that at the next session of the Diet, the enslavement of the peasants should again be recognised as the law of the land."15

In order to find this text I found myself typing the word "roasted" into the search box. Punishment such as this could best be described as "medieval" and yet it seems the only separation on the level of sensation between such barbarism and "modern warfare" is that today it is not discriminating. To put it bluntly, countless children in Palestine have now quite literally been roasted. And artists in Sydney, it seems, in particular, are being very careful about not posting anything suggesting that a genocide is happening because some of the major donors of the museums and galleries have ties to Israel. None of them will be as well remembered as Cranach and Dürer. And though I don't demand that they sacrifice themselves for the ultimately hopeless ends of a global peasantry, I also can't help but hate them all sometimes. It feels as though a lot of us are going through this vacillation. And the majority of work being produced under these conditions doesn't even move me to hate, it is so empty. Total emptiness may indeed be the safest investment. Meanwhile, I feel this emergent class divide as it becomes accepted that I have summarily doomed myself to what is posited as unskilled labour, and the hypocrisies of the art bureaucracy are making many of my relationships feel untenable, where advancing the idea of my squalor and/or dysfunction seems to somewhat soothe the consciences of the terminally craven.

Whether or not the accounts of the DDR exaggerate the radicalism of Grünewald via his application of paint (which is obviously a ludicrous claim), his long-supposed political inclinations can hardly be dismissed wholesale. All the artists of the DDR, and indeed, any of us with strong instinct against injustice, particularly in wealth distribution (regardless of the way we might self-define) could quite easily rally under the banner of Ratgeb, an accomplished artist in his own right. Golan makes no good argument to the contrary. And yet the poetic sympathies evoked by Grünewald speak to something which I perceive to be much more relatable. And this is because I am not a fighter on the front lines who is about to be drawn and quartered. As much as it could well be argued that one of the great innovations of the most pernicious actors of the early 20th century was hardly to have done away with medieval levels of torture, but rather to dissolve their specificity in the name of greater dehumanisation. Regardless of affiliation, the horrors that human beings inflict on one another are expressed in his work to raw and devastating effect, a form of "realism" that has seemed to be definitive of modernity. The reason that Grünewald has continued to break hearts through the centuries is this appreciation of pain, painted by an ultimately pathetic figure. Someone who was to have lost his livelihood, something still almost unquestionably tied to his sympathies with the peasantry, and to have ultimately died of it, through the slow creep of destitution.

1 Engels, Friedrich. The Peasant War in Germany. 1st edition. Oxford: Routledge, 1926. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646633. 40

2 I favour Quinn Slobodian’s definition of “Neoliberalism”, which is explained by Phd candidate Josh Patel here: "Slobodian reiterates this argument that neoliberal cannot be equated usefully with ‘laissez-faire corporatism’. Instead, for Slobodian neoliberalism can be conceived of as a form of governmentality which is concerned with the preservation of the free operation of markets through strong central legislation by states or institutions. The rightfully free actions and subjective valuations of individuals are represented collectively in the market which, through the price index, provides the optimum distribution of goods possible. Attempting to control or interfere in the operation of the market is a recipe for inefficiency and autocracy. Instead under neoliberalism, the powerful centralising tools of state infrastructure, such as the exercise of the rule of law, should be directed towards the maintenance of the stable conditions necessary for the efficient and free operations of the market." https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/ghcc/blog/quinn_slobodian_globalists/

3 http://thecityasaproject.org/2012/07/the-measure-of-turmoil-durers-monument-to-the-vanquished-peasants/

https://germanhistorydocs.org/en/from-the-reformations-to-the-thirty-years-war-1500-1648/albrecht-duerer-s-memorial-to-the-peasants-war-1525 (this account even has the peasant atop the monument likened to a resting Christ)

4 Erwin Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, (Princeton University Press, 1955), 233

5 Ibid, “From a most interesting report unfortunately not included in the "Unterweisung" (1685) we learn that Dürer favored the classical roof, with a slope of little more than 20 degrees, against the steep Gothic one; and his ideas about city-planning-laid down in his Treatise on Fortification and possibly connected with one of the earliest "slum-clearing projects" in history, the Augsburg "Fuggerei" of I5I9/20– reveal his familiarity with such modern theoreticians as Leone Battista Alberti and Francesco di Giorgio Martini. But his designs for capitals, bases, sun-dials and whole structures such as the tapering tower to be placed in the center of a market place are anything but classical. He also describes, among other things, triumphal monuments to be composed of actual guns, powder barrels, cannonballs and armor, yet accurately proportioned more geometrico. When celebrating a victory over rebellious peasants, these monuments are to be composed of rustic implements such as grain chests, milk cans, spades, pitchforks and crates; and a humorous extension of this principle leads-"von Abenteuer wegen" ("for the sake of curiosity")·- to an epitaph in honor of a drunkard, consisting of a beer barrel, a checkerboard, a basket with food, etc. It should, however, be noted that these absurd contrivances met with the approval of François Blondel, and that at least one of them-a slender monument crowned by the figure of a wretched conquered peasant (fig. 314)-may have been inspired by certain fanciful designs of Leonardo's (fig. 315).” 257

6 Morrison, Tessa. “Albrecht Dürer and the Ideal City.” Parergon 31, no. 1 (2014): 137–60. https://doi.org/10.1353/pgn.2014.0050.

7Walter, Rolf, Maximilian Kalus, Uwe Cantner, Hans-Walter Lorenz, Michael Hutter, Fritz Rahmeyer, Guido Buenstorf, and Horst Hanusch. “Innovation in the Age of the Fuggers.” In The Two Sides of Innovation, 109–25. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01496-8_6. 122-123

8 Golan, Tamara. “Mit Dem Kreidestift Und Farben: Revolutionizing Grünewald in the German Democratic Republic.” Art History 46, no. 2 (2023): 310–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12714. 310-343

9 Golan, 316

10 Golan, 336

11 Golan, 332

12 Golan, 325

13 B. Krylov, “Preface” in Marx Engels On Literature and Art. Progress Publishers. Moscow 1976; https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/subject/art/preface.htm

14 W.G. Sebald, trans. Michael Hulse, “Max Ferber” in The Emigrants, London: Vintage Books, 2002, p.17

15 Engels, Friedrich. The Peasant War in Germany. 1st edition. Oxford: Routledge, 1926. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646633. 90