“Cultural Capital/Sun King (Hipster Fascism)” MMXXIII. Found Masonite, acrylic.

I called the exhibition that I made this painting for “Retrosynthesis (Ekphrasis): The Cognitive Elite” and this entire blog has essentially been dedicated to writing about the works in it, with a few minor digressions (lol). This painting was originally inspired by reading a “viral” article “Among the Reality Entrepreneurs” by James Duesterberg, which details an apparently seamless transition of the hip, art-adjacent New York scene known as “Dimes Square” into reactionary right-wing politics at the launch of internet alternative “Urbit”, another bizarre initiative of billionaire Peter Thiel, actually advocating for a more literal form of “Technofeudalism” with the establishment of digital fiefdoms. The article details the weirdness of the convergence of the art scene with the “nerds” of Urbit, ultimately rejected by the art scene with its cultural capital, but also that there is some shared agenda between the two, both organised by hierarchies that privilege the ultrawealthy.

The exhibition was held in one room of a community-based, council-lead public art exhibition, in a weird, mouldy, colonial sandstone building that the council is set to transform into studios. They like to speak to it being the oldest building in the area, which, like many such impositions in the “Australian” colony, is spectacularly unimpressive both structurally and historically. I think maybe 20 die-hard friends turned up to see this exhibition over its course, and the greater batch were on their way to the brilliant poetry series, “&&” curated by Mitchel Cumming and Rachel Schenberg at the nearby Barratt House, another council arts initiative in a free “historic” space in faint disrepair, though one whose provenance at least involved a silent filmmaker. I recall a particularly funny exchange I once had with an arrogant through in no way wrong French/Turkish architect that was enlisted in designing the “Central Park” development in Chippendale, complaining that they were having to work around “historic” building elements that were maybe a hundred years old as though they were precious, though they were just average bits of the old brewery, crappy colonial remnants imposing “history” on the stolen land of an ancient culture. I probably was dismissive of the whole project, because I remember him saying something about how everything can’t be art spaces, as there really were quite a lot of them in the vicinity at the time, to which I replied something to the effect of “fuck art spaces, I just love the enormous hole in the ground,” referring to the then current state of excavation, a crater that must have gone four stories down. Where the habit of utlising and harvesting everything for investment once permeated the city, this great dead zone was oddly soothing. Now most spaces in the city are underutilised, with work becoming more remote or non-existent and rent ever increasing, as ownership becomes more concentrated and the people who own all the space do not need to rent it out.

Two famously petty tyrants/

Peter Thiel bankrupted the website “Gawker” for revealing that he is gay. Aside from this new monarchism, he is involved in maybe every bizarre libertarian cause there is.[1] Louis XIV gaoled a nobleman for extravagance (having a better house than him) and then used his architect, Louis Le Vau, painter, Charles le Brun, and landscape architect, André Le Nôtre, to build Versailles. This story is told in The Man in the Iron Mask, part of a larger work and the final of the adventures of the Musketeers written by Alexandre Dumas père, a lamentation for a bygone era of honour and chivalry in the name of the King, written as a serial in the 1840s post-revolutionary France by the grandson of an Afro-Caribbean slave. Louis XIV is known for consolidating the divine right of Kings and sweeping away vestiges of the feudal system (as well as making lots of wars) … and also his contribution to the arts. The Musketeers saga begins during the reign of Louis XIII, which roughly coincided with the beginnings of French colonialism, and the theme of nostalgia for a world on the brink of modernisation was pretty common fare in post-revolutionary France. In a review of yet another adaptation of the Three Musketeers as well as a recent biography of Dumas’ father by Tom Reiss entitled The Black Count, Boyd Tonkin explains that another common theme in Dumas’ oeuvre are characters such as D’Artagnan, hellbent on avenging a wronged father. Dumas’ father Alex Dumas had been subjected to racialised abuse for accompanying a white woman to the opera in Paris, rejected his aristocratic lineage, taken the name of his formerly enslaved mother and become a general in the French Revolutionary armies, at a time “when it looked as if the upheavals of 1789 would usher in a golden era of racial equality.”[2] Described as a 6 foot 2 “Hercules”, Alex Dumas would even be mistaken by the Egyptians as the leader of the French Revolutionary Army, standing beside the famously less imposing Napoleon. It is suggested that it was their rivalry that lead to Alex Dumas being left in prison in Egypt for 2 years after his capture, which broke his health. In any event, by the time he had returned to France, all black officers had been expelled from the army by Napoleon. He died shortly after his return, when Dumas was just a child.

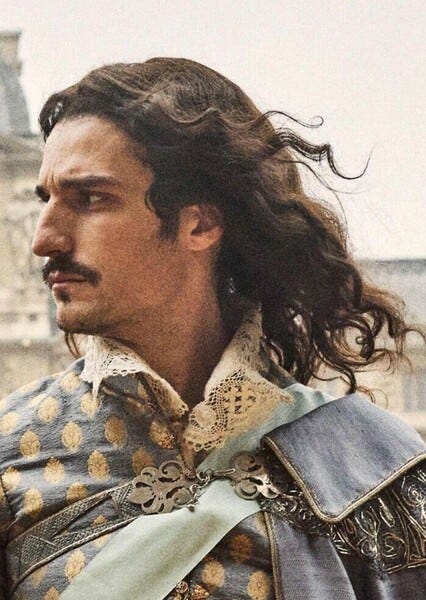

Romances such as those written by Dumas were hugely popular and successful and somewhat derided by the intellectual class of the time, heavily invested in the “realist” novel, though both essentially turned against modernisation as it was coming to be constructed. It is weirdly easy to forget that the word romance is literally derived from the word Roman, the word for novel in French is “un roman”. The conceit of “realism” is actually something born from what we would call the gothic, altogether bleaker and more northern, remnants of the feudal system that came to be associated with democracy as a counternarrative to empires past. Romances can take all kinds of forms, but the weirdest among them might be the ones that look to a glorious past of chivalry, even where, throughout Dumas’ oeuvre, royalty and politicians are looked upon with some ambivalence, the disappointing mortal components of an ideal of France that can never exist. The only nobleman that really comes off quite well within the Musketeers saga is the handsome Duke of Buckingham, in real life, famously almost certainly gay with King James I of England (King James VI of Scotland). Nonetheless, I always loved those books. I went to the cinema to see a recent French remake of The Three Musketeers, featuring a very impressive cast of French actors, many of whom I have long found incredibly sexy and learned exactly nothing from the experience except that I really have a type:

The Three Musketeers: Vincent Cassel

The Three Musketeers: Louis Garrel

The Three Musketeers: Romain Duris

The first part of a video series on DIS art by Paul Lemaire and Vincent Burger entitled “The Television Will Not be Terrorized,”[3] introduces a pretty weird television spectacle in 1988 in which actors, journalists and lawyers staged a “trial” of Louis XVI in order to allow the French people to decide, via phone poll as well as an early French version of the internet, whether he should (have) be(en) guillotined. The people voted overwhelmingly, and fairly astoundingly, toward his acquittal. This basically tracks with the new revival of monarchism within North American extreme right and/or conservative thought. Though, it should be said that the extraordinary figure of the defence council, in the televised display, an actual lawyer, Jacques Vergès famous for defending terrorists, may have played some role in their convincing (I am very much looking forward to seeing more of the series and watching the documentary on Vergès “Terror’s Advocate”). “The Television will not be Terrorized” begins with a quote from Mencius Moldbug, the nom de plume of American blogger Curtis Yarvin, co-founder (along with philosopher Nick Land) the anti-egalitarian and anti-democratic philosophical movement known as the Dark Enlightenment or neo-reactionary movement, which has close ties to the Thiel cinematic universe:

“As for the Charismatic leader and would-be king, he must combine the two most important ingredients of hypermodern political communication: irony and sincerity. This entire project of 21st-century monarchism (on the blockchain!) is both utterly ironic, and completely sincere.

Every part of making it happen will feel like a joke. The result, however, will be completely real – both sincere, and irreversible.”

A fascination with figures such as Yarvin is almost a feature of Post-Internet Art, which seems to concern itself almost primarily with right-wing reactionaries on the internet, perhaps as a result of “the left” allegedly not being able to meme (lol). In looking for the link for Brad Troemel’s “The Left Can’t Meme” [4] I come across an article of the same title from a “right” perspective in UnHerd magazine, one of the bastions of “free speech” owned and championed by a hedge fund founder, though one that quite unusually countenances alternative viewpoints. The thing is, that free speech is pretty much a right wing concern these days, and you should find that unsettling.[5] The article on left vs. right memes by Ed West, begins (after quoting the spectacularly sexist author Milan Kundera) by stating:

“Humour has long been a magic ingredient in unlocking political change. In the medieval court, jesters had an almost unique privilege in being able to tell the monarch what he didn’t want to hear, and were often tasked with presenting bad news. In totalitarian regimes humour was a daily act of undermining the regime, to the extent that on Stalin’s death 200,000 of the Gulag’s 2.5m population were there for telling jokes.”[6]

I am not sure of the exact breakdown of the Gulag population; but the point about court jesters is quite fun, except that the privilege wasn’t entirely unique as medieval social relations tended to be a bit more complex than we are usually lead to believe, and making fun of those in power was not unusual, and in no way threatened the hierarchy. In a recent ABC interview with Eric Idle, that Sky News thug that took over from Barry Cassidy on Insiders, listens rapturously as Idle regales with a story about Charles, now King, turning up at Billy Connelly’s house near Balmoral to a group of comedians taking the piss out of him, which he did most enjoy. Idle says that King Charles II even asked him if he would be his jester. Idle suggests that he quite rudely refused, but as he and Charles both went to Cambridge, Charles has a wonderful sense of humour. How charming that our king can laugh at himself. Comedy today, hey? Still it does not diminish the “Constitutional Peasants” scene from Monty Python’s “The Holy Grail”, from which we remember: “strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government. Supreme executive power derives from a mandate from the masses, not from some farcical aquatic ceremony.”[7] Something we all apparently need reminding of right now.

The function of comedy, like art, is generally ambivalent, fortifying, certainly, maybe even a reason to go on, but ambivalent. This is of course, the argument made by Mikail Bakhtin in Rabelais and His World, the publication of which was delayed for 30 years having been written as a doctoral thesis in Stalinist Russia. It was mentioned by cultural theorist and author Catherine Liu in the new vodcast “Doomscroll” headed by sociologist of the internet Joshua Citarella (who also featured in a painting in the “Cognitive Elite” exhibition). Citarella raises the prevalence of North American monarchists to Liu’s obvious bemusement and amusement, not shared by Citarella who is more familiar with the territory. Later in the interview, when discussing the way that academia is funded and the monopolies that even it reproduces (in the kinds of subject matter, the privileging of representation over ever talking about class) Liu reflected that perhaps because there already are essentially a selection of kings in charge people just don’t see another way, to which Citarella explains, that that is indeed the argument of these new North American monarchists. Liu mentions the carnivalesque championed by Bakhtin, and how the humour of the peasantry in every way resembles the memes that Citarella is so fond of, laughing in such a way as affirms the power structure (Citarella is momentarily taken aback). I had a very good laugh at what is essentially a point I have been trying to make for a decade, taking tens or hundreds of thousands of words, that Liu simply quipped as an aside (I love her).

Liu was recently in Australia; the conversation between her and the very smart and talented Wiradjuri anti-disciplinary artist, Joel Sherwood Spring in Brisbane/Meanjin was interesting enough to reach my ears in Sydney/Gadigal and Sebastian Henry-Jones’ ears in Melbourne/Naarm, but she never came to Sydney because there was no forum for her to speak here (Felix McNamara contacted me to look for a place, but we all drew a blank after the Power Institute proved uninterested if not disinterested). There is literally no place for broader debate within this city. The consensus-enforcing labours of the Professional Managerial Class have effectively appropriated the platform of the “left” here, in lock-step with the interests of monopolistic capital, mocking the perceived stupidity and immorality of the right while we all seem to get poorer by the day. And this is because, in some instances what is being promoted by this strange revisionist right is actually completely understandable, sympathetic and even desirable, basic needs met that are ever further away from ordinary people. In the aforementioned interview, Citarella mentions an article in Vanity Fair written by James Pogue,[8] amidst a conservative conference featuring JD Vance in 2022 (and thus before Vance was appointed as Donald Trump’s potential Vice President) in which, much of what is discussed is that a family should be able to raise children on a single income, which seems pretty reasonable to me.[9] Vance is a constant figure of fun, sometimes for good reason, the racist dog whistling over Haitian immigrants being a case in point. But there is nothing new in blaming immigrants for class problems created by very wealthy people like Vance’s supportive former boss Peter Thiel. It has been pointed out that the lies about Haitian immigrants have been largely unsuccessful as a strategy compared to similar right-wing goading in previous election cycles, either because the media have figured out that such idiocy is best ignored or (I think more convincingly) there is not much of a media left.[10] Of course, anyone objecting to immigration should probably begin with protesting against the various wars and destabilising initiatives the west involves itself in, or by trying to pressure major corporations to mitigate climate change, because mostly people do not want to have to leave their homelands and homes and friends and family.

The weirdness of the Vanity Fair article largely pertains to it being a genuinely good piece of journalism in which groups of people that are constantly mocked are made human. Pogue writes about the new partner of Curtis Yarvin who was a formerly liberal writer who replied to his advertisement, essentially looking for a smart woman to settle down with. She wanted children, stability, things basically unavailable now to those in the Professional Managerial Class, where we have casual academia, the gig economy and fukbois. Of course, all sympathy becomes absurd when it is revealed that the reason she turned to the right was the “Black Lives Matter” movement... it was really scary…? There has always been reason to suspect racist tendencies within liberal circles, but it has all come to the surface through the Palestinian genocide. I have seen some incredible racism within institutions, and I am whiter than fucking white. Obviously, I cannot speak to the experience of others, so let me draw your attention to this widely-read piece detailing the problematic practices of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) by their former employee Beau Lai (none of which seem to really have been addressed since its publication): https://medium.com/@lillylaimui/working-at-mca-australia-this-is-what-happened-to-me-it-does-not-exist-in-a-vacuum-75642ce8c4b3

In the way that racism is always confusing and bizarre, Vance is married to an Indian immigrant and practising lawyer, despite all his calls for a “traditional” family, apparently hearkening an imagined past that never quite existed. Feminism is derided by the right for all kinds of reasons, this new brand particularly takes issue with women in positions of power and even in the workforce, and yet certain forms of “feminism” are certainly, in some part culpable for the work culture we find ourselves in, the kind of “have it all” feminism that, in a coded way, basically denigrates the labour of housework and childrearing, in many ways contributing to the primitive accumulation of women’s labour. It was certainly a win for the capitalist class when the workforce doubled, and our leisure time began to shrink such that no one had the time to question the way things are. In some dark corner of the internet, I recently spied a meme about Gloria Steinem being a CIA operative and had a very good laugh. Steinem, it transpires, is quite open about having worked for the NSA against the communist threat in the early part of her career. I am fairly ambivalent about Steinem’s role in such initiatives, happy to give the benefit of the doubt regarding what her vision was for liberation, hoping that she might perhaps have agreed that an end-goal of feminism is that men and women should be able to choose the division of labour, perhaps each working three days a week in an office, supermarket or factory, looking after their homes and each other the rest of the time, in a universe of comfortable homes resembling the middle class of the mid-20th-century in the West. Except that in the 2016 lead up to the selection for the Democratic Presidential Candidate Steinem actually suggested that young women were promoting Bernie Sanders and not Hillary Clinton because they want to be closer to the boys. Fucking second wavers, hey? (Meanwhile when Steinem was working for the CIA, Silvia Federici was working for an organisation called “Wages for Housework”, real feminists do not reinforce capitalism.)

What, was interesting for me, in looking into all of these histories, alongside savouring the Doomscroll interview in fifteen minute lunchbreak intervals, was that there was a total convergence between when Liu pinpoints the decline of the American working class, in 1972, and the end of a certain type of CIA covert operation, which happened when the front organisations distributing funds to all kinds of cultural and political groups were exposed, operations like the one Steinem participated in. When they couldn’t win hearts and mind through arts and state-sponsored grassroots politics the new move against the working class was to send working class jobs offshore, under the guise of creating cheaper products for the betterment of American society, further immiserating impoverished populations around the globe. Within the West, this almost immediately resulted in stagnant wage growth, unemployment, cheaper goods and services and much more expensive housing. And an obvious decline in the quality of cultural output.

A few remarks on the present:

In my last blog I thoughtlessly misconstrued the origins of a new space that was engineered by Mike Hewson repeating the notion that it was brought to you by the Nielson family, where in fact they simply own the building that is due for demolition, and Hewson negotiated to use the space until that time, which he has done before with other studio space that has proven invaluable to the ecosystem of the Sydney art scene. I was aware that the more commercial concerns in the new space at Redfern, as well as those in artist studios seem to be paying Sydney-style rent and that maybe the Artist Run Initiatives are operating at reduced cost. I am not aware of the exact financials and won’t comment further in ignorance. I would honestly be happier for everyone if the space was cheap or free, which is not to say that I would refrain from questioning how the money works or making fun of the whole thing, though I thoroughly respect everyone involved, lol. The three art spaces are really promising, MEGA is one of the new ARIs (something we need more of) run by two smart, interesting young people also involved in Schmick and currently showing some really nice wall paintings by Tommy Carmen, you should check it out (the current exhibition at Schmick, by Lewis Doherty is also excellent). You should also pop into Minerva, which is the “commercial” concern though it seems much more a labour of love by someone who has a career in an entirely different industry and consistently loses money on this wonderful passion project. Having shown with Minerva, I am obviously biased, lol, but I have always really loved their programming because it seems lead by inclination more than anything, and seems to stay above the fray of art world positioning and lame professionalism. The next exhibition at Minerva will be Phillipa Hagon, at MEGA, Alex Gawronski, both of whom I admire both as artists and human beings. My point about the “Nielsonscene” was rather a reply to something that probably wasn’t worth it, some cosplay communist speaking in favour of the philanthropic exploits of billionaires as an inherent good, where I find it to be basically ambivalent. I would like spaces to be free, but I suspect that it would come at too high a cost. Talking to Iakovos Amperidis the other day he was tracing when 55 Sydenham Road received government funding, which should be basically neutral, to when it lost its soul. I know that he and Elise Harmsen sunk a ridiculous amount money into that place, regardless, to keep the gallery and studios running, just for the sake of a community. Art and artists can be heroic, but usually settle for stupid institutionalised pseudo-rebellion. I don’t know what the answer is where money is concerned, but I suspect that liberation of art and artists can only come through a society in which the basic needs of the majority are met.

I came up around the end of such a period in “Australian” history. In 2012 I was provided with a studio in Rozelle, a fifteen-minute bus ride from the city, through Serial Space, then operating out of Chippendale, which is essentially in the city, for the development of work for their Time Machine Festival, which was made possible by Kensington Street Studios. Kensington Street Studios was adjacent to or perhaps even set up by the developer working on the immense “Central Park” building, with its embarrassing name hearkening New York, and complimentarily cheesy futuristic “hanging gardens of Babylon” vibe. Both the studio space in Rozelle and the Kensington Street space were slated for demolition and so we were allowed to make some very weird art there. I paid $20 per week for that studio because the building was being demolished anyway, I suppose the space was essentially valueless in that interim and uncertain juncture. Aside from Serial Space and the short-lived Kensington Street there were maybe 5 ARIs in Chippendale around that time, along with a few venues for independent music: now I don’t know of any. Now there is only Phoenix, which hosts live music by a relatively professional class of artists for free via a ballot system in architecture resembling a downscaled, post-apocalyptic colosseum, which is an initiative of billionaire Judith Nielson; and in terms of contemporary Art there is White Rabbit which showcases Nielson’s collection of Contemporary Chinese Art. A friend, John Wilton, who lives in Beijing (where he is studying something like Confucian philosophy), was telling me sometime late last year about an art/music festival on a frozen lake (which was apparently not so easy to project video onto, lol), and it sounded absolutely amazing, I guess because of the seeming spontaneity, the sense of community as much as any outcome. I do not frequent White Rabbit because Nielson’s taste does not particularly appeal to me, but it could be just that it looks a bit too much like “big art”. This is not to say I am ungrateful of these initiatives, as it is incredible to have such access to the Contemporary Chinese art market so close to home and especially fascinating that it very much resembles the work of the Western art market. It is obviously noble to try and share great art, music and architecture with everyone, but I still don’t think that anyone should have that much money. As far as the work coming from our closest neighbours, I prefer the work and the ethos coming out of 16 Albemarle Project Space, where politically charged and community-lead work seems to be prioritised, certainly, though the work is just genuinely interesting aesthetically, also.

Stay Gluten Frei

Ella Sutherland, in her wisdom, very often alerts me to the world around me, which I will tend to ignore in pursuit of, for example, a functioning understanding of the theories of Henri de Saint Simon, and the other Saturday night was no different. As we walked through the streets of Potts Point (formerly the “vice” suburb of Kings Cross) which was in the midst of a City of Sydney sponsored “street party”, I was telling Sutherland of a recent Time Out article that made me feel as though I was living in a parallel universe, in which Sydney’s Chippendale was listed among the 7 best suburbs in the world, citing, of all things “Spice Alley”, a group of mid-range to upmarket restaurants designed to look like a quaint pan-Asian streetscape, carved out of what were the warehouses of the Kensington street studios, which I believe is an initiative of the developers responsible for the “Central Park” tower. To my relief, Sutherland was as mystified as I. Meanwhile, in our immediate surrounds, and Sydney being Sydney, no booze was to be consumed outside of licensed venues at the “street party”. Said venues were most clearly demarcated with a truly awe-inspiring proliferation of crowd-control equipment that resembled less a “party” and more a military exercise aimed at quelling a spirited population (bearing no resemblance to the locals), and indeed, may well have been a front for such an exercise, because who knows what they are testing on us now. Like battery pigs in their pens, the upper middle class white people of the area drunkenly danced to “I am everyday people” (they were not everyday people) $25 negroni in hand as Sutherland and I found ourselves herded into one of these enforced economic zones in our haste to find our way into the backstreets to escape to get dinner in Chinatown. By the time we had eaten dumplings and had one beer, the whole "party" was over and the last stragglers were some 20 year olds, one unaccountably eating a baguette, though one so obviously a dodgy Australian supermarket staple as to be more properly called a "bread stick". We both breathed a sigh of relief to discover that the young man with the offending gluten was a German tourist. No one eats carbs in Potts Point. Sutherland remarked that everyone here just keeps willingly giving their last rights away because (the white, middle-class) Australians (represented by the Potts Point population) have never really experienced hardship, that they are basically ignorant of how bad things can very quickly get from here. I had to concede that I am largely out of step with what the more privileged members of the art world understand to be happening, but there is no real reason that I should have such a markedly different viewpoint as I am of the same stock. No one should need to be persuaded to stand up against wholesale slaughter or even rampant injustice and inequality by being made aware that it could happen to them, and yet it really does seem like a lot of people and a lot of artists think that they are somehow different and immune to what is happening to a lot of the world now. I have experienced first-hand what happens when wealth is concentrated, when those who make and manipulate the law use it to deny the labour and the personhood of other people. My father left us with nothing, and he was very rich. Watching the dehumanisation of my mother through the court system and through my father’s years of manipulation taught me everything I needed to know about asymmetries of power. I have lived extremes of privilege and lived for a decade under the poverty line with a debilitating chronic illness, and still remained among the most privileged people in the world because of where I was born. But it was only recently, in a job-training video, of all things, that I learned that hypervigilance, once thought of as symptomatic of the dysfunctions of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder has latterly been reassessed as a perfectly reasonable coping mechanism when confronted by certain situations where harm is likely. My triggers are coercive control and financial abuse, so it makes sense that I would end up in the artworld trying to work it all out, lol.

And things have got so much worse in my lifetime; artist studios are now spectacularly expensive in Sydney. It seems as though everyone pays upwards of an eye-watering $200 a week on top of their already exorbitant rent, such that work has to be profitable, has to appeal to anyone can afford it, even as the middle class, who once might have enjoyed and even bought artwork, shrinks to nonexistence. This can only get worse as the wealthiest get wealthier, as they have done exponentially since the pandemic, and look to invest, which is to buy up all the available real estate. A friend relayed how they had been speaking to a developer mate and mentioned the cost of studio space, which said developer found very impressive as it works out to be a very high yield for space, especially space with few or no amenities that can be in a state of disrepair, especially when one considers how many empty offices and factories there are in this town at this juncture. But as artists we are taught to be grateful for anyone letting us exist.

Meanwhile, the dramas churned out for the streaming services we receive to our ever-receding living pods focus on luxury or at the very least the international Airbnb style. Even stories about underprivilileged and racialised youths seem to involve scholarships recognising their superiority to the communities from which they have been drawn. It could be the reason so much Post-Internet Art looks so ‘80s, because we are all nostalgic for working class representation, of the kind that doesn’t try to impose our betterment. I think that you should be able to live comfortably with healthcare and a roof over your head while working in a supermarket three or four days a week, which has weirdly become a radical perspective.

Presently, I am laid out with terrible period pain watching an utterly terrible Netflix film, which is making me feel really happy about the decline and fall of Western civilisation as I think a Hemsworth, playing a venture capitalist, explains to a group of (necessarily silly) writers on an unfortunately relatable if unrelatably luxurious writers retreat in Morrocco (like some post-colonial fever dream), that it is fine to invest in coal extraction because we still need power and renewables can’t be responsible for all of it. They are rightly convinced. As this character’s flirtation with a recently single older woman played by Laura Dern deepens comes, possibly, one of the cinema’s most cringe-inducing scenes of all time, in which, with her psychic gifts, bestowed upon all writers, though none could come up with a convincing counterargument for the exponential growth of power consumption, she divines that his high school nickname was “the big O”. The point at which his character is forgiven for his upcoming affair is when his intelligence is insulted by his girlfriend who mentions that “he only reads Sports Illustrated” in front of the other writers playing a clever game citing famous novels like notches in the bedpost, featuring Gustave Flaubert’s revenge on bourgeoise taste Madame Bovary. It is obviously a “mom porn” film, but when did mom’s turn their gaze exclusively to fucking venture capitalists? Were they just the only people willing to fund this trash? As someone whose initial targeted facebook ads were for men’s 19th century style nightgowns from a company called “Bonsoir of London”, it is only right that I address nostalgia for the past, which, in my case, is very much tied to nostalgia for a future. I have always lamented the time travel nonsenses of erotica, as returning to times when women were literally counted as property does not seem either clever or sexy to me… but staying in the present is somehow worse now. I have been threatening to move into more populist territory and monetise my love of hate-watching with a podcast entitled “Burning While the World Streams” but I feel dirty having related even this anecdote. Of course, a ban on streaming video would do more for the environment than any number of solar farms, not to mention the incredible energy consumption of Blockchain that really does not need to exist, it is a fucking pyramid scheme and thus it should not be surprising that Thiel is into it. I will head back to the library shortly to type incredibly aggressively and loudly due to all the years I spent working on Olivetti typewriters (the power, the majesty, the untold strength of these fingers), while I scowl at young people talking. Where my luddites at?

Mixed Media

In an article entitled “I’m Running Out of Ways to Explain How Bad This Is” staff writer for The Atlantic, Charlie Warzel, laments the growing surge of conspiracy and mistrust in (necessarily) internet-based news. Certainly, the fallout around Hurricane Milton in Florida, with crazed conspiracies resulting in attacks against the disaster responders is deeply troubling, as is the general lack of news since it was abandoned by the Meta group, and since so many newsrooms have purged their staff. But I think the piece is mostly interesting for the role that old media such as The Atlantic have played in skewing narratives, where the horror stories described by Warzel are entirely relatable to any of us who have stepped outside the orthodoxy of the Professional Managerial Class (i.e. the narratives driven by journalists, academics, all of those who define culture):

“What is clear is that a new framework is needed to describe this fracturing. Misinformation is too technical, too freighted, and, after almost a decade of Trump, too political. Nor does it explain what is really happening, which is nothing less than a cultural assault on any person or institution that operates in reality. If you are a weatherperson, you’re a target. The same goes for journalists, election workers, scientists, doctors, and first responders. These jobs are different, but the thing they share is that they all must attend to and describe the world as it is. This makes them dangerous to people who cannot abide by the agonizing constraints of reality, as well as those who have financial and political interests in keeping up the charade.”[11]

Place this mediascape against Edward Said’s description of Flaubert’s last (unfinished) novel, as a mocking of a very Christian world view parsed as secular by the Enlightenment:

“But it was not just any science he (Flaubert) mocked: it was enthusiastic, even messianic European science, whose victories included failed revolutions, wars, oppression, and an unteachable appetite for putting grand, bookish ideas quixotically to work immediately. What such science or knowledge never reckoned with was its own deeply ingrained and unself-conscious bad innocence and the resistance to it of reality. When Bouvard plays the scientist he naively assumes that science merely is, that reality is as the scientist says it is, that it does not matter whether the scientist is a fool or a visionary; he (or anyone who thinks like him) cannot see that the Orient may not wish to regenerate Europe, or that Europe was not about to fuse itself democratically with yellow or brown Asians. In short, such a scientist does not recognize in his science the egoistic willpower that feeds his endeavours and corrupts his ambitions.”[12]

And so, we return to mid-19th century France, as political ground, which is so bizarrely, utterly relevant to the present. I often think of the “Haussmannisation of Paris” as one of the most decisive acts of modernisation towards an utter military-industrial complex, where Baron Von Haussmann razed many of the vestiges of the medieval city for the sake of the famous Boulevards (that you could drive a tank through). The main tourist area remains the Medieval remnant of La Marais, because cities designed for military occupation are arguably less charming. As described by associate professor of geography, Deborah Cowen in her book The Deadly Life of Logistics: “Haussmann was given extraordinary powers directly from Napoleon (III) in 1853, and he boldly exercised that authority in a massive campaign of creative destruction.”[13] Haussmann’s main inspiration for this order, the precursor to polite and sanitised urban and suburban spaces around the globe, was from a book written by Marshal Thomas Bugeaud called the “gardener of Paris” for his love of these new clear and suburbanised “green” spaces, La Guerre des Rues et des Maison (The War of Streets and Houses) (a decidedly creepy title). Bugeaud’s successful occupation of Algiers involved razing much of the city to prevent radicals from emerging through ancient alleyways. Until Bugeaud’s impositions the rebels had actually been managing to hold back the French army, as resistance movements are generally very successful unless entire populations are eradicated, the ends of colonialism are necessarily genocidal. It is further explained by British-Israeli Architect and Director of Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths, Eyal Weizman that: “As a royalist who opposed the Industrial Revolution, which he thought was physically and morally toxic, Bugeaud personified the anti-urban attitudes of the French Restoration.”[14] Weizman further mentions this new application in an article entitled “Walking through walls: Soldiers as architects in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict”[15] discussing the military tactics employed by Israeli soldiers in Palestine in 2002.

Maybe a year after being investigated for bias after privately sharing a meme in which President Biden was labelled a “war criminal” on her private social media, tech journalist Taylor Lorenz recently left the Washington Post to go independent. A decent article by Kyle Chayka in the New Yorker points out that Lorenz doesn’t aspire to be a writer but an “internet personality”, in a way that reads as disparaging, also concluding that her new platform looks a lot like ordinary good journalism. I share Chayka’s reservations about the prevalence of “raw copy” in this turn towards a “creators’ economy”, where journalists churn out stories that would have been much improved by editors. (Everyone needs an editor, especially me.) I consume a lot of this new media “content” and, more than anything, it is annoying, an overproliferation of talking heads all talking about the same issues. But this is probably the efficacy of someone like Lorenz in acting as “personality”, a sort of aggregator of trends that already exist, as opposed to an opinion writer. This is, after all, hardly distinct from being a broadcast journalist, where Lorenz has proved a very worthy interviewer, for example, with far-right “creator” Chaiya Raichik who before the (disastrous) interview had been wreaking havoc inflaming tensions over LGBTQI content in school libraries (and who showed up to the interview in a t-shirt with Lorenz’s crying face on it).[16] I would say that this is evident in some of the best work by both artists and media/internet personalities of my generation, where the work becomes a kind of education design in a world in which education is under threat, probably more from the Professional Managerial Class then the right wing. The hysteria promoted by someone like Raichik, after all, only sensationalises real issues inherent in an increasingly authoritarian bent in the traditional media and universities given over to corporatisation. After “that meme” WaPo investigated bias in Lorenz’s journalism, but reached no conclusions. She never wrote for them again. And there is no suggestion that WaPo similarly investigated the veracity of her claim, which one would imagine could be quite easily established through the connection of President Biden’s infamous funding of Isreal’s military exploits. After all the ICJ did rule that “Israel's occupation of Palestinian territory, encompassing the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, is unlawful under international law” and that Israel’s actions amount to “annexation”. Apparently, the word “bias” is now applied to inconvenient truth. A Substack that I am newly subscribed to arrives in my inbox with the heading “Impossible Dream Realized: Media Falls Below Congress in Trust Survey (Gallup's annual confidence survey shows 68% of Americans will not relieve themselves on a journalist in flames)”.[17] But this is, in many ways, a process that has been going on since the press began, and so it is perhaps encouraging that the propaganda has become obvious to the wider population.

OVERWRITTEN

“This sense of intimacy is deepened by that worshipful respect for the particular which makes the picture a little world inexhaustibly rich, complete in itself and irreplaceably unique. It is a truism that northern Late Gothic tends to individualize where the Italian Renaissance strives for that which is exemplary or, as the phrase goes, for “the ideal,” that it accepts the things created by God or produced by man as they present themselves to the eye instead of searching for a universal law or principle to which they more or less successfully endeavour to conform. But it is perhaps more than an accident that the wia moderna of the North — that nominalistic philosophy which claimed that the quality of reality belongs exclusively to the particular things directly perceived by the senses and to the particular psychological states directly known through inner experience — does not seem to have borne fruit in Italy outside a limited circle of natural scientists…”

-Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting.[18]

The preceding passage is largely about the work of Jan Van Eyck, the 15th century Flemish painter that was such an innovator in the field of oil painting that he was even wrongly credited by 16th century art historian (painter/architect) Georgio Vasari as having invented it.[19] I have actually been attempting to write about the 17th century Dutch Republic, which I will not get to in any substantial way until the following blog. Sometimes it seems as though all roads lead to post-revolutionary France. Naturally, to get to the paintings of the 17th century, I thought it prudent to read Panofsky’s “Early Netherlandish Art”, (mostly about work from around the 14th and 15th century) to understand how what is referred to as “The Dutch Golden Age” came to be. Because Northern Europeans from fairly early in the second millennia had quite a different “perspective” from the Italians, in that painters such as van Eyck would extend the picture plane, late gothic works quite often folding into surrounding architecture. Van Eyck would paint marble frames around some of his works, creating works that exist in the world, the progenitors of what would come to be understood as “realism” which often is mistaken for reality. Before becoming aware of Filipo Brunelleschi’s advances in oddly mathematical renderings of two-dimensional space that advanced correct perspective (which Panofsky liked to point out is basically redundant considering the human eye is round), van Eyck painted the incredible Arnolfi Portrait (1434), which has four “vanishing points” and a vision of a world which seems to carry on beyond the frame. Northern painters were already forming their own perspective before it was formalised in the Renaissance, but subsequent to becoming aware of the necessity of a singular “vanishing point” which is to say that all work must come from the perspective of a single individual, van Eyck would fall in line. The difference between the two traditions, nevertheless carried on, in which the renaissance romanesque presented these romantic ideals that even came to be seen as quite silly or counterrevolutionary by art historians such as Théophile Thoré (in 19th century France) as against the dark versions of reality innovated in the north and conscripted to the cause of the working classes, with appropriate Protestant modesty.

Jan Van Eyck, “The Arnolfi Portrait”, 1434.

In his own time, van Eyck, was highly respected as an intellectual as well as an artist, it was not merely skill that was admired by his contemporaries but knowledge and intelligence. To a certain degree, the invention of writing and its irreducibility within the monotheistic tradition (“in the beginning there was the word”), always created a hierarchy wherein visual communications and representations were seen as lesser than the written word, “false idols” even. Though, in the calligraphic traditions of Islam, at least, there was always some allusion to the visuality of the written word that doesn’t quite seem to exist within Christian thought, where the alphabet and written language are taken for a transmission of information somehow outside of time and space. And yet it is really only from the beginning of The Reformation that the new iconoclasm, casting the artists out of the temples, that image-makers become denigrated, placed beneath the knowledge-workers who strictly apply thinking through alphabetism. This is an antiquated ideal that is everywhere perpetuated by the traditional media and universities, while the transmission and receipt of knowledge has fundamentally shifted over the last century, and now more decisively than ever. Those that labour with their hands are basically suggested to be stupid in the same way that it took sign language a bizarrely long time to be recognised as a language because the gestural is seen as something lesser.[20] Most painters are not writers or analytical in the way specific to me; but good painters, like all good craftspeople are exceptionally intelligent gesturally and poetically. The old hierarchies have become absurd. But the old hierarchies haven’t even existed for that long in human history, and have never been universal. Painters know things that could not be learnt any other way, things that are pointless to try to communicate in words, such that my PhD is literally one long joke.

RETROACTIVE

After spending too much time with the trend towards a new monarchism, I came to ask:

“Is this strange turn toward a representative god on earth to change the way we perceive and appreciate art, or is art, in fact, already ahead of this trend, where such astronomical sums are allotted to such a vanishingly small number of artists and works that the great bluff of democracy does not even seem to apply?”

When I began to write this text I began with:

“Who now, would imagine that the writing of history should be limited to the exploits of kings and queens, or their equivalent modern plutocrats? And yet, this is the very measure by which we are lead to judge art history- the production of “genius”, and it is very much a production.”

A statement that perhaps would have been relevant still when I was undertaking my undergraduate degree, but so much and yet nothing has changed within institutions. My casualised colleagues and I talk about how the course materials (where we are given any) are exactly the same as what we were taught, work predominately from the 1960s to 1980s, and yet it now seems that we are supposed to also strip the concept from the conceptual, to reveal the purely formal appreciation of works that began as anti-aesthetic, in the mode of a “New Materialism” of the spiritual immanence which is supposed to negate history, politics and context. So, this “genius” persists while we are fighting for our survival on the margins of the institutions, until we even forget why and for what reasons the “great” artists of the past were valourised. John Berger spoke about this in the 1980s, that the great painters of the Western canon all rebelled against their contexts, and that this is perhaps the only tradition in which that is true, because making for the market has always sucked.

Meanwhile, the painting that first comes up under the Wikipedia entry “Dutch Golden Age Painting” is Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid”, 1658-1661.[21] This is quite strange when one thinks of the many great painters of that era, perhaps especially Rembrandt Van Rijn, whose work has been consistently popular since its own time (and for good reason). This is not to diminish the achievements of Vermeer but to allude to how recent in history is the attraction to a painter who lived and worked more than 350 years ago. Vermeer’s work was not popularised or even really known until the mid-to-late 19th century, and yet in the intervening years his popularity has only grown. His work and even his life have even apparently been the subject of several presumably mediocre popular novels, including one I was forced to read in my TAFE high school equivalency course, Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier (1999), that became the subject of a movie featuring one Scarlett Johanson (2003). What I can mostly recall from that work was some rather clumsy foreshadowing involving a dropped knife, allusions to the poverty of the Vermeer family, exasperated by his perfectionism and the long time it took him to paint (which seems contextually dubious as the Dutch were quite prepared to pay for time spent and even were more likely to prize work that conformed to their “protestant ethic” as such). I liked learning about the guild system, and that people had trades in painting tiles and so on, which I thought was probably the best way to make a living, definitely better than a lot of the alienated labour immediately available to me. I also recall something about the lower status of the Vermeers in Dutch society as Catholics, and (the interesting part) the writing that was about the hand-making of all the paints, the grinding of the highly expensive semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli, to produce blue pigment. I am not sure if that novel was when I was first made aware of Vermeer, but I was impressed enough by the formal qualities, the darkness of the work, and the subject matter that I suppose his work has always been a particular favourite of mine, if partially for the historical interest. I have an old Olivetti typewriter company calendar hanging on my wall with the page open at his remarkable “The Art of Painting” in which, likely with the aid of a camera obscura, he challenges single point perspective, which could not render such a tiled surface, something also alluded to in “Las Meninas” by Diego Velasquez.[22]

Johannes Vermeer, “The Art of Painting”, 1666-8.

Even so, it was not until 2014 that I first viewed Vermeer’s work at The Frick, in Manhattan, a museum that was the former home and collections of a literal “robber baron”. I remember thinking that it was incredible that Frick had collected 4 Vermeer paintings since there must be so few in existence (34-35 can be comfortably attributed). I walked past a tour guide or teacher explaining the works to a group of adolescents in private school uniform and became decidedly irritated that they were offering a purely formalist reading, talking about things like skill and beauty, without any reference to the subject matter, which seemed to be the whole goddamn point of Vermeer: that he painted the common people. It was only recently that I realised that this perspective was largely engendered by the English teacher at the TAFE and not necessarily anymore a commonly held view (though, it was perhaps engrained in the reading in the aforementioned novel, I have no desire to go back to read it for the sake of fairness). The reading being somewhat particular to the teacher also seems likely to me as it was the same teacher who also recommended reading Gustav Flaubert’s A Sentimental Education, a ruinous work of 19th century “realism” if ever there was one, which is to say revolutionary democratic in subject matter, a life that is a series of failures and disappointments. It transpires, though, that through what almost amounts to a second campaign of revisionism in art history or the art present, the original reason for the renewed interest in Vermeer, his being plucked from two centuries of obscurity, has been undermined by institutions and private collectors that owe their “good taste” to the work of an important art historian whom I had never heard of before beginning to research this very phenomenon. Because several of Vermeer’s work works were contributed from various collections to the Exposition Universalle in Paris, in 1867,[23] as a result of the tireless efforts of brilliant art critic, passionate collector and advisor, and literal revolutionary, Étienne-Joseph-Théophile Thoré, better known as Théophile Thoré or Thoré-Bürger. From 1849 after joining an “abortive insurrection”,[24] Thoré was forced to live in exile in Brussels as William Bürger (the name alone speaks to the bleakness of the situation, lol) until an amnesty in 1860 lead him back to Paris. The Frick collection is also the resting place of another work of the “Dutch Golden Age” that was very nearly lost to history before finding its place in the collection of Thoré, which apparently he gazed upon to his last hours, Carel Fabritius’ “The Goldfinch” (1654),[25] (which has since been made the subject of a book by Donna Tartt and subsequent film).

In an article from a series from 1952 on art critics Thoré is credited as founding the modern “scientific” form of art history, what could be understood as a materialist reading in which the wider context is examined, Thoré being among the first to bemoan the notion of beauty without substance. In this same article by French diplomat (and apparent friend of Roland Barthes), Phillipe Rebeyrol explains that: “Before even attempting this historical work, a complete, exact, and methodical inventory had to be drawn up of the artistic inheritance of Europe. It was to this preliminary task that Thoré set himself. If it had not been for the interruption in his political activity, for the misfortunes and leisure of exile, he would never have discovered Vermeer. In such ways, disappointed romanticism gives birth to modern scholarship.”[26] 15 years later, Highly esteemed (Harvard) art historian and curator, Jakob Rosenberg, in a book entitled On Quality in Art divides his study into chapters containing centuries from the 16th to the early 20th by writing about presumably the most prominent art historians/critics of each, or at least the most interesting to Rosenberg: the 16th century, for example is dedicated to the still widely famous Vasari, whose Lives of the Artists still adorns the book tables of all the Italian Museums… the 19th century is given to Thoré.”[27] Obviously, it was after this time that analysis of the production of art history fell out of favour among schools of contemporary art, reminding me of a line I quoted in another blog, that: “the success of business propaganda in persuading us, for so long, that we are free from propaganda is one of the most significant propaganda achievements of the twentieth century.”[28] In an 1998 article by Frances Suzman Jowell, a historian of the work of Thoré and Théodore Géricault, basically acts as reply to the catalogue of a then-recent exhibition of Vermeer’s works where the curator seemed to actively attempt to sideline the work of Thoré, going so far as to suggest that Vermeer was not rediscovered by Thoré but rather William II, King of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg from 1815-1840, because he owned one Vermeer painting (lol and double lol).[29] It is an interesting politic, to restore Vermeer to the aristocracy that never claimed him as superior until 200 years after his death. Jowell writes:

“I have been prompted to return to Thoré’s much celebrated “rediscovery” of Vermeer in response to the unexpectedly dismissive treatment of the French critic in the catalogue of the 1995-1996 Vermeer exhibition, in Ben Broos’ otherwise scholarly catalogue essay, “Un celebre Peinjntre nomme Verme[e]r,’” as well as some of the scattered references to Thoré concerning the provenances of particular paintings.

This attitude would have astonished Thoré’s contemporaries, for by 1866 he was unequivocally acknowledged as the unrivalled expert on Vermeer on account of both his art-historical publications and his efforts to interest collectors in Vermeer’s works. Several critics paid tribute to his “rediscovery” of Vermeer in reviews of the 1866 exhibition.”[30]

This is not to suggest that there has necessarily been a wilful sidelining of the work of Thoré, especially as, when properly contextualised, his “socialist” politics prove to be rather less radical than at first appearance, but rather to point out the dangers of the disjuncture between art history and theory, and indeed of history theory and practise.

Thoré was a follower of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon, better known as Henri de Saint-Simon, who certainly contributed to the movement toward democratic ideals, but whose politic has elsewhere been described by Karl Marx as “a new industrial feudalism.” [31] In fact other followers of Saint-Simon would go on to found the merchant banks responsible for building the Suez Canal and rebuilding Algiers (after the French destroyed much of it to quell the Algerian resistance)… creepy.[32] This is not to say that Saint-Simon did not harbour some remarkably progressive views, especially concerning women’s rights, and the rights of working people, which were even found instructive by Marx and Friedrich Engels. The French Revolutionaries and surrounding thinkers, were, after all, champions of the working classes. Nonetheless, Saint-Simon’s “hierarchical socialism” was to promote a rational society lead by certain members of the middle-class, such as industrialists, as opposed to the idle wealthy like landlords (makes sense he is no longer in vogue)… the second group elevated to a position of importance would be scientists, and the last, and perhaps most reassuringly for those of us who have dedicated our lives to something so spurious, was that of artists, as the three pillars of the vanguard of social advance. It is almost as if Thoré fell victim to the same empty flattery that fills galleries with incredible statements about how representative nepotism is ending racism and climate change. In 2009 economist Riccardo Soliani concluded that Saint-Simon’s vision for the future would be realised some 100 years after his death in “managerial and monopolistic capitalism.”[33]

It seems to me that this very weird silence around certain figures and ideals that in fact created the art market that we know today is an extension of this process of secularisation, where thought is robbed of its religiosity or even of any socio-political imperative, as neoliberalism, a close relative of the protestant ethic, is “not political” and certainly not religious (lol again). Thoré’s criticism was highly influential, he had access to museums and private collections where he researched artists such as Vermeer, buying what he could afford himself, but broadly encouraging the collection of these works. He championed the social realism of the Dutch Golden Age both as a Romantic and alongside the move towards democratic realist novels of 19th century France. He also felt that the world should be on the precipice of a whole new way of making art, such that, shortly before his death he was also the first to recognise the importance of a whole new generation of artists such as Monet and Renoir. Rosenberg’s description is particularly instructive:

“In his analysis of Rembrandt in particular, and elsewhere, he stressed that great art requires more than mere description of life and nature, that individuality and originality come into play, that the great artist sees nature according to his inner imagination and inserts poetical feeling and even a sense of mystery. It is true that in the Salon of 1861 Thoré called Millet and Courbet the two master painters of the show and predicted for them a secure place in the future, but he also said that neither of them would ever reach the greatest heights; obviously he felt that their work lacked something essential for the highest level of art. On the other hand, it might be held against Thoré’s critical faculty that he failed to recognize the genius of the young Manet, whose works he saw and reviewed. Here was a case in which he seemed handicapped by his "humanitarianism" which resulted in his opposition to the principle of l’art pour l’art. Thoré’s great slogan was "Art for man" and he found Manet's content too neutral. He demanded deeper participation in life and nature, not "pure painting" alone. Shall we really blame him for this attitude, or say that it inhibited his critical faculty? It all depends. We shall discuss at a later point whether "content" comes into play as a necessary component of the judgment on quality.”[34]

I never did find out if “content” is a necessary judgement of quality, and I realise I really should stop trolling the Ivy League, but they make it too easy. I may have actually laughed out loud upon reading the description “handicapped by his “humanitarianism”” (I make my own fun). Of course, it turns out that Thoré did to an extent, champion Manet, especially upon the request of the poet Charles Baudelaire, which is mentioned in a reproachful tone similar to Jakobsons, by Rebeyrol.[35] Thoré also was to defend Manet when “Olympia”(1863) initially scandalised the art establishment, though only half-heartedly as the faces of the humans in the painting were treated in much the same way as the elements of still life.[36] One might say, in other words, that the subjects of Olympia and her African maid were dehumanised. Thoré’s guiding principle was “l’art pour l'humanité”, n’est-ce pas? Thus, we find again, the prescience of the writing of Thoré, whose problems with Olympia seem remarkably contemporary. I am not sure of his feelings towards Courbet’s “L’Origin du Monde”(1866) but I actually love that painting, so whatever. I also am very fond of this latter-day reply from William Meadley “La Fin du Monde” (2023):

So, the modern sense of art history, in which what could be called a materialist application of art history, removed from classical aesthetics and the singular search for beauty, progressed throughout 19th century France in measured response to post-revolutionary democratic ideals, as well as new theories taking revolutionary objectives further toward a socialism specifically antagonistic to the capitalist order. This is probably the underpinnings of how we understand the at least ostensibly inaesthetic art of late capitalism. But we have been losing ground ever since the practise of art history was completely abandoned under the guise of universalism, beginning with the mania for “the new” from the beginning of the 20th century, but finally concluded this century. The spell is broken by reading into how things came to be. The antecedents for this market, also the major subject of Thoré’s investigation, was history as experienced by everybody, not just the privileged. To understand the coded racism and classism within the art system it is imperative that we ignore the propaganda of the Professional Managerial Class which claims that we in the West have a global, secular focus and see the continuity between it and the imperialist order. Perhaps the omission of this narrative of the production of modern and then contemporary art is not so hard to understand then. These, after all, are not times in which to centre humanity, and certainly not common or impoverished humanity. So, it is in fact, not so difficult to understand how an art historian apparently so sympathetic to the operations of the late 20th century and looked upon as so vital to the mid-20th century, is now all but passed over. It may well be that we have reached the point of something worse than simple “managerial and monopolistic capitalism.”

[1] (including sea steading, in which a bunch of white men hope to live in cities that float atop the ocean and sail between different versions of political utopias to try them all out – I recommend Jacob Hurwitz-Goodman’s documentary on the subject: https://jacobhg.com/seasteaders-trailer/)

[2] https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/features/the-role-of-race-in-the-life-and-literature-of-alexandre-dumas-the-episode-that-inspired-the-man-behind-the-musketeers-9065506.html

[3] https://dis.art/the-television-will-not-be-terrorised

[4] Brad Troemel even made a vodcast called “The Left Can’t Meme” https://www.patreon.com/posts/left-cant-meme-77324335

[5] Digging deeper into my sources I read an almost characteristically bitchy article in The Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/media/2023/oct/28/loud-and-uncowed-how-unherd-owner-paul-marshall-became-britains-newest-media-mogul) “To UnHerd’s supporters, the site’s success simply speaks to the quality of its writing and editing, the curation of idiosyncratic voices and a growing appetite for “unheard” perspectives. “We are not aligned with any political party, and the writers and ideas we are interested in come from both left and right traditions,” UnHerd assures its visitors. “But we instinctively believe that the way forward will be found through a shift of emphasis: towards community not just individualism, towards responsibilities as well as rights, and towards meaning and virtue over shallow materialism.” …which sounds terrible. The author, Samuel Earle goes on to talk about the nefarious financial activities of the publication owner, mentioning that it is only the right that is seeing any media growth as publications are flailing in the contemporary media landscape, mentioning that UnHerd is unique in showcasing a range of perspectives, but countering an umbrella organisation that has made room for Yanis Varoufakis as well as right-wing figures I have never heard of, via ad hominem attack against the owner, in the midst of a world in which capitalism actually can’t be avoided. Back on track, Earle speaks to the championing of conspiracy and climate change denial and the hysteria over trans people’s rights to exist as the rather more distasteful exploits of this bastion of “free speech”.

[6] https://unherd.com/2021/08/why-the-left-cant-meme/

[8] https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2022/04/inside-the-new-right-where-peter-thiel-is-placing-his-biggest-bets

[9] James Pogue, “Inside the New Right, Where Peter Thiel Is Placing His Biggest Bets (They’re not MAGA. They’re not QAnon. Curtis Yarvin and the rising right are crafting a different strain of conservative politics.)” Vanity Fair, April 20, 2022. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2022/04/inside-the-new-right-where-peter-thiel-is-placing-his-biggest-bets

https://www.garbageday.email/p/america-s-various-horrible-uncles?_bhlid=9bc6f8a0d3765fd092a3a2178552b457c75851cb&utm_campaign=america-s-various-horrible-uncles&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_source=www.garbageday.email

[11] I’m Running Out of Ways to Explain How Bad This Is

What’s happening in America today is something darker than a misinformation crisis.

By Charlie Warzel The Atlantic

[12] Edward Said, Orientalism

[13] Cowen, Deborah. The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade, University of Minnesota Press, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=1765501.

Created from usyd on 2024-10-16 00:06:01. P.189

[14] https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/22/bugeaud.php

[15] https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/walking-through-walls

[16] https://www.poynter.org/commentary/2024/taylor-lorenz-chaya-raichik-libs-tiktok-interview/

[18] Panofsky, E. (1966). Early Netherlandish painting. Volume 1 : its origins and character. Harvard University Press. P.8

[19] Panofsky, p.180

[20] Rotman, B. (Brian). (2008). Becoming beside ourselves the alphabet, ghosts, and distributed human being. Duke University Press.

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_Golden_Age_painting

[22] Heath, S., MacCabe, C., & Riley, D. (n.d.). Brian Rotman, Signifying Nothing: The Semiotics of Zero (1987). In The Language, Discourse, Society Reader (pp. 101–127). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230213340_8

[23] Jowell, Frances Suzman. “Thoré-Bürger’s Art Collection: ‘A Rather Unusual Gallery of Bric-à-Brac.’” Simiolus 30, no. 1/2 (2003): 54–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/3780951. P. 55

I am doing my best to refrain from doing further research into the history of “Old Masters” exhibitions for the sake of my sanity. Allusion to the British inspiration in Jowell’s “Vermeer and Thoré-Bürger: Recoveries of Reputation.” Studies in the History of Art, no. 55 (1999): p.51

[24] JAKOB ROSENBERG. “The Nineteenth Century: THÉOPHILE THORÉ (W. BÜRGER) [1807–1869].” In On Quality in Art, 67-. Princeton University Press, 2023. P.69

[25] Jowell, Frances Suzman. “Thoré-Bürger’s Art Collection: ‘A Rather Unusual Gallery of Bric-à-Brac.’” Simiolus 30, no. 1/2 (2003): 54–119. 58

[26] Rebeyrol, Philippe. “Art Historians and Art Critics-1 Théophile Thoré.” The Burlington Magazine 94, no. 592 (1952): 196–200. http://www.jstor.org/stable/871064. 197

[27] JAKOB ROSENBERG. “The Nineteenth Century: THÉOPHILE THORÉ (W. BÜRGER) [1807–1869].” In On Quality in Art, 67-. Princeton University Press, 2023.

[28] Alex Carey, and Andrew Lohrey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy: Corporate Propaganda Versus Freedom and Liberty, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997, p.21

[29] JOWELL, FRANCES SUZMAN. “Vermeer and Thoré-Bürger: Recoveries of Reputation.” Studies in the History of Art, no. 55 (1999): p.48.

[30] Recoveries of rep 39-40

[31] Soliani, Riccardo. “CLAUDE-HENRI DE SAINT-SIMON: HIERARCHICAL SOCIALISM?” History of Economic Ideas 17, no. 2 (2009): 21–39. P.21

[33] Ibid, p.38

[34] Rosenberg ibid, p.93

[35] Rebeyrol, ibid, p.200

[36] Ibid.

Share this post