After almost a year of exclusion after writing about certain conflicts of interest, the directors of both of the organisations implicated, namely ARTSPACE and The Art Gallery of New South Wales, have now resigned, without extended explanation, but with many a sycophantic tribute. There have long been rumours around each institution. One can only hope that the rumour of potential job losses at AGNSW, for example, to be just ordinary public-sector rumblings. When I wrote into the way that money works in that place, I became very perturbed by what seemed to me a very tenuous position the gallery is in following the renovation, a public institution so dependent on donation that its objectivity is very doubtful. I was going to write a bit about the major donors, but the information is publicly available. Of course, a lot of money also went into the renovation at ARTSPACE. I still haven’t set foot inside, but I hear that it now also features a lovely function centre. Meanwhile, the international residencies are long gone, leaving this city even more than usually cut off from the world and from any meaningful cultural debate. This is an Americanisation of art, away from what was a local model of public investment, towards philanthropy that further separates the haves from the have-nots. I still can’t believe that this was allowed to happen without community consultation and consensus. I, for one, am not sad to see either director leave.

I am almost finished in writing my PhD, “an original contribution to knowledge” and I am not certain that art is the production of new knowledge, so much as the reminder of our incapacity to really know anything. The enforced secularisation of art, which has everything to do with a Protestant, Northern European world view that is in practise not at all as secular as it appears, has reduced art to productivism, where it cannot hope to find a “purpose” enough to justify its existence. Parallel to this is the view of the written word’s superiority over understanding as received through gesture and the visual realm. So, I wound up writing a lot more than I thought that I would about Protestant Aesthetics as an offshoot of what Max Weber called the Protestant Ethic. I came to spend a lot of time thinking about Human Rights Law and its relationship with the same worldview, the same closeness to a new form of dominance via economics. It seems to me that the aesthetics employed in Late Capitalist Art have only lately expanded to include the “rest of the world”, but that they remain almost secretly and yet irrevocably tied to Northern European austerity, both in the visual and conceptual realm. The further I went back in history the closer I came to the present, which I hope to finally convey through this last text in the series (though with the possibility of a few minor supplements to come).

"Pronk: Print Screen (Cast-Light Horology)", MMXXIII. Oil on (discarded) glass. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

There are antecedents I have written to in the beginnings of the Reformation during the 16th century, but I have only touched on the conflation of art with the market, which happened very rapidly when the Stock Market was invented in the 17th century in the Dutch Republic, to service the Dutch East India company, the origins of the corporation as we know it, as well as a pragmatic, industrial colonialism. And thus the two images conflated in this painting are Tacita Dean’s silver gelatin photo “Lord Byron Died” of 2003 wrapped onto the “Holbein Bowl”[1] in Willem Kalf’s “Pronk Still Life with Holbein Bowl, Nautilus Cup, Glass Goblet and Fruit Dish” of 1678. Kalf’s paintings, most probably produced with the aid of a camera obscura, look almost more real than reality, through particular liberties he takes, something in the light and the contrast in darkness. They have been said to be a challenge to the beautiful objects that they convey, somehow above the skill of the craftsmen who made the originals. As paintings, they are also essentially impossible to reproduce to anything like the quality of seeing them in person. Paintings of what has for some time been known as the “Dutch Golden Age” were the first European works to be made for a market, rather than commissioned by a patron or church. Kalf’s objects were drawn from all over the then burgeoning trade Empire of the Dutch Republic.

Dean’s recording of 19th century graffiti, which came about as a failed attempt to follow in the footsteps of exiled poet George Gordon, Lord Byron, in Greece, taken on the precipice of the takeover of digital photography, simultaneously demonstrate Dean’s love affair with the film stocks that have so rapidly become all but obsolete, and with visual art as a medium secondary to the written word, properly exercised in its description. Dean’s fixation with the material of photography, in the form of film stocks becomes a lament for the tangible expression of ideas. Where it has been said that Dutch society did an astounding amount of its epistemological discovery through pictures, Dean’s process fixates on the possibilities of the chemical process rather than its representative qualities, a faith in the alchemy of the mechanical world that can only be nostalgic. They are both strange works largely for what they leave out, impregnated with their own colonialism and simultaneously mournful of it, of Empires that made the whole world their material. Kalf’s works, Pronkstilleven, or luxury still life are always somehow hollow, and more so than the more prosaically Calvinist works of the better known Vanitas artists of the era, whose moralising is contained to individual responsibility. Dean may lament the now unstoppable process of encodement, where the artisanal process of discovery is frustrated by the nature of command (both in the sense of computation and in the limitations imposed by the private ownership of the artistic means of production). And this history, alluded to through these two works, “realisms” so perfect as to be mostly inarguable are yet visions of an always limited perspective, telling the story of European Capitalist art that was to be digitised into recognisable forms that are somehow only referent of art and never its embodiment.

ORAL HISTORY

An area in which I have been hitherto remiss is in having failed to offer a “podcast” or audio version of my texts, which I will set about remediating. It was a very silly thing not to do given that basically all artists are neurodiverse, lol (including yours truly). I currently have a lot of anxiety over podcasts because of my need to finish my goddamn paper, but also because I am making up for lost time as regards all the years where it was very difficult for me to read, so I am always looking for the transcript for pure efficiency, and because being able to read really difficult texts all day gives me untold joy. In my defence, I did once produce a video where my text was read aloud by the United Kingdom version of the Microsoft Word “James” voice which a friend joked was basically indistinguishable from the monotone of my own delivery (in my previous incarnation as a hell-raising performance artist). So, I figured if anyone wanted to hear me recite the text they could just cut and paste to Word and set the AI to British.

I started thinking about poet and independent curator Judy Annear’s reading group years ago, when I happened to be in the midst of one of my relapses with M.E. and utterly unable to decipher words on the page. I explained that I had read the text out loud and recorded it so that I could listen to it and process it and artist and academic Sarah Rodigari responded angrily, and typically comically, when discovering that I had made said recording but had failed to send it around to the whole group, like I had been holding out on her. So I guess some people like my the sound of my voice, if not as much as I do. I did train my voice for years for the purposes of performance/recitations. An old lecturer of mine, Martin Sims, used to share literature and performances with me in my undergrad, including Jacques Brel’s incredible live performance of his poem/song “Dans le Port d’Amsterdam”, where his intensity makes the slightest movement of his little finger read like a slap across the face. I trained myself to sing it in my admittedly very rusty French. The poem about the tragic lives of Dutch sailors is actually weirdly fitting for the following text (this is the part where I burst into song).

Dans le port d'Amsterdam

Y'a des marins qui chantent

Les rêves qui les hantent

Au large d'Amsterdam

Dans le port d'Amsterdam

Y'a des marins qui dorment

Comme des oriflammes

Le long des berges mornes

Dans le port d'Amsterdam

Y'a des marins qui meurent

Pleins de bière et de drames

Aux premières lueurs

Mais dans le port d'Amsterdam

Y'a des marins qui naissent

Dans la chaleur épaisse

Des langueurs océanes

-Jacques Brel, Dans le Port D’Amsterdam

And so, we come to the “Freedom of the Seas” or Mare Liberum produced as an anonymous pamphlet in 1608, though it was written by Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius (Hugo de Groot) at the behest of the world’s first corporation, a truly multinational enterprise, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC (The United East India Company), and commonly known as the Dutch East India Company. The Liberum Mare was one of the first charters to recognise universal human rights. While an important document it could also, arguably, be construed as an immediate origin of an “international law” being codified and demonstrated on the behalf of imperialist powers evoking morality as a justification for violent oppression. Where Dutch colonial rule differed from the other imperial powers then terrorising native populations of Africa, Asia and the Americas, was that it was undertaken on behalf of the aforementioned corporation, and even proved to act against express instruction from the government of the Dutch Republic.[2]

The Dutch Republic was founded when 7 provinces of what was then the Spanish Netherlands, revolted against Spanish rule in 1579. In the lead up to what is (somewhat contentiously) known today as “The Dutch Golden Age”, which roughly lasted from the beginning of the 17th century to the mid-18th, the spoils of sea trade had been divided up roughly between Spain and Portugal. Philosopher and historian of law and politics, Johannes Thumfart explains:

“In his bull Inter caetera of 1493, Pope Alexander VI divided the world’s oceans, donating half to the Spanish and half to the Portuguese. Such political-theological intertwining of papal power and Portuguese-Spanish claims can be traced back to, among other sources, those treaties which the Iberian kings and the papacy had concluded during the process of the reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula. Within the context of the reconquista and the conduct of a ‘just war’ against the Muslims, the validity of the papal grants had been based upon the concept of a theological and political supremacy of the pope over non-Christian territories.”[3]

The Christian World’s very self-understanding was formed in opposition to the Islamic World, with which it had constant contact and whose innovations it had benefited from in every way. Like, do you know what might have been better than the Dutch Golden Age? – The Islamic Golden Age (which lasted from the 8th to the 13th Century). The term itself is problematically European, and certainly falls under the category of “Orientalism”, but the period that it seeks to describe was nothing short of extraordinary, for it is essentially formed the foundations of what we understand as modernity. I have alluded to the invention of complex mathematics and perspective therewith via Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, but the innovations happened across all disciplines, developments in medicine, education, economics, literature, art… Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham is said to have invented the scientific method making him the first true scientist… Ibn Khaldun wrote comprehensive sociological and historical accounts taking class into consideration, a polymath of early Social Sciences… scholars even preserved the great European texts of the Classical period through translating them to Arabic.

I keep thinking how weird it is that the middle east is continuously promoted in the West as this uncivilised “other” when so many civilisations, ideas and religions were born there. As ancient sites are bombarded indiscriminately in Lebanon, the earth that bore so many of the fruits of A vast array of human endeavour, I walk up to Schmick Contemporary in Chinatown to see an exhibition by Tarik Ahlip, “Kara Toprak”.

Tarik Ahlip, “After The Drinking Scene”, 2024. Plaster, pigment, sand, 23k gold leaf

83 x 64 x 3.5 cm

Ahlip’s beautiful plaster works are evocative of ancient traditions, skilled enough to appear almost to have been ripped from some mediterranean altar, without being classically derivative. I honestly can’t remember how long it has been since I have set eyes upon a work and felt so reluctant to take them away. The work is accompanied by his text written about his visit to Lebanon at the beginning of the year.

The full effect is heartbreaking. (I am listening to the song from which the exhibition takes its title as I write, and I am crying.) The last day to view the work is this Saturday the 30th of November from 1-4pm.

The Netherlands under Spanish rule were the site of the largest number of religious executions of that era of the Inquisition, the history is said to have haunted the republic long after independence.[4] The official religion of the newly formed Dutch Republic was Calvinism, but only about 20% of the people were Calvinist, and the government and citizenry were notably tolerant of various faiths, of other Protestant Christian religions such as the Lutherans and Mennonites, but also to Catholicism and Judaism. In fact, during the Inquisitions in Spain and Portugal, many of those of the Jewish faith fled to the Dutch Republic. It was from this background that one of the great progenitors of Enlightment thought, Baruch Spinoza was to emerge, to be excommunicated from the Jewish community for his radical athiesm, which was also broadly tolerated in the Dutch Republic. It even seems as though the same tolerance may have been extended universally, where Grotius wrote:

“It is heretical to hold that infidels are not the owners of the property that belongs to them. And the act of snatching from them, on the sole ground of their lack of faith ... is an act of thievery and rapine no less than it would be if perpetrated against Christians.”[5]

The often-evoked tolerance, of course, does not mean that all were on equal footing within the Republic, for example, Catholics were considered of lower status, Jewish citizens were limited to certain jobs, and Jewish men were not allowed to marry Christian women. “Tolerance” also never extended outside the republic, such that whether or not Dutch legal jurisdiction would immediately lay claim to the property of those in the Islamic world, as the Pope had ruled for the exploits of the Catholic powers, those peoples and all other “infidels” could hardly expect to hold on to their generously recognised property in the face of the Dutch military machine. The ruling was rather that they were free to trade with whomsoever they chose (presumably before their property, territories and persons were taken from them by force). For, from the time that the various shipping interests from different parts of the Dutch Republic were consolidated into the VOC, the goal was the monopolisation of the spice trade. And universal human rights were very much founded as justifications for “privateering” or state/company supported piracy, which was fairly commonly practised against the Spanish and Portuguese. Grotius would also basically invent the notion of the justness of the pre-emptive strike.

On the surface, through the employment of these new “rights” the VOC was remarkably successful. An article by founder of “GeniusWorks”, formerly the head of the world’s largest Marketing agency, Peter Fisk relates:

“The peak value of the Dutch East India Company was so high, that it puts modern economies to shame.

In fact, at its height, the Dutch East India Company was worth roughly the same amount as the GDPs of modern-day Japan ($4.8T) and Germany ($3.4T) added together.

Even further, in today’s chart, we added the market caps of 20 of the world’s largest companies, such as Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, ExxonMobil, Berkshire Hathaway, Tencent, and Wells Fargo. All of them combined gets us to $7.9 trillion.

At the same time, the world’s most valuable company (Apple) only makes it to 11% of the peak value of the Dutch East India Company by itself.”[6]

What Fisk failed to account for is that investment bank Blackrock, whose fortunes have only risen after pandemic, “manage” assets well in the range of the VOC, and as of this month, October 2024, boast of assets totaling $11.48 trillion dollars,[7] (and has even been compared to the combined wealth of the GDP of Germany and Japan). Its CEO, Larry Fink, recently told investors that the outcome of the United States of America’s General Election doesn’t matter. It is becoming less and less controversial that success is now seen as total dominance/monopolisation, and it is deeply disturbing (a recent study suggests that more Americans trust Amazon and Google to “do what is right” than they trust the police, teachers and the news media).[8] In the four years of the Biden Administration, the wealth of Billionaires in the U.S. grew by a staggering 88%.[9] And yet the Biden administration made some positive changes in what had become an almost inevitable trend towards unchecked “mergers” and the inevitable price gouging, after Joe Biden’s appointment of legal scholar Lina Khan to chair of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Khan was responsible for example, for a lawsuit which challenged the patent on inhalers such that the price of life-saving asthma medication dropped from around $500 to $35; and has become the target of all those who would see wealth and power ever more concentrated in the hands of the few.[10] Because, of course, this is a nightmare for major tech companies, whose business model is monopolisation. Elon Musk recently boasted that Khan would be sacked under a Trump administration.[11] But Khan was equally unlikely to retain her role under Kamala Harris, many of whose donors directly oppose her monopoly-busting agenda. Somewhat bizarrely J.D. Vance is an admirer of much of Khan’s work, along with a group of MAGA conservatives sometimes referred to as “Khan-servatives” as many on the right become more interested in anti-trust legislation (i.e. breaking up monopolies).[12] Of course, Vance is still good friends with his former employer, Peter Thiel who as a famed Libertarian is directly opposed to government intervention.

For an example of the somewhat contradictory politics of Vance, take Bitcoin. Thiel is a sometimes cautious supporter of Bitcoin because he says it “exists outside the purview of central banks” and “it is a store of value like gold and a hedge against central banks' monetary policy”.[13] Vance also has something like $500,000 worth of Bitcoin. Bitcoin is famously volatile in terms of valuation and its data centres cause massive environmental destruction for the sake of a speculative economy that maybe isn’t interesting to anyone who isn’t afraid of government regulation.[14] A “market bubble” traditionally describes the overvaluation of a product in relation to its intrinsic value. For example, in his article on the VOC, Fisk further alludes to the famous “Tulip Mania” of 1635 as “the first market bubble”, where, due to rampant speculation, asset prices of tulips in the Dutch Republic far exceeded the intrinsic value of tulip bulbs. The collapse in the tulip market caused no significant impact on the Dutch economy as one would expect of a market bubble today. Bitcoin, of course, does not seem to have any intrinsic value, such that I struggle to understand it as anything other than pure ideology, a Libertarian holy grail. A recent targeted advertisement on Instagram provides a view into an alleged environmental solution in which the heat from data centres built for mining bitcoin is being used to grow hothouse tulips in the Netherlands. I am not sure if I was “targeted” with this because advertisers understood the incredible mirth that I would experience, but for whatever reason it was supposed to garner my ever-important attention, I am sincerely grateful for the laugh.

However, it is Fisk’s quite incredible explanation of the VOC that is of the most interest to us here, (i.e. the legacy of the company from the perspective of someone who seems to believe that monopolisation at any cost is an inherent good):

“Companies like (…) the VOC (…) were granted monopolies on trade, and they engaged in daring voyages to mysterious and foreign places. They could acquire exotic goods, establish colonies, create military forces, and even initiate wars or conflicts around the world.

Of course, the very nature of these risky ventures made getting any accurate indication of intrinsic value nearly impossible, which meant there were no real benchmarks for what companies like this should be worth.”[15]

The description of military exploits, which were quite literally the exploitation, enslavement and genocide of non-European populations seems fairly blasé, to say the least, and yet the same kinds of exploitations basically continue now at an industrial scale. What is interesting about the Dutch Golden Age is the seeming lack of interest of the public, but mostly as a view to how someone in the future might assess the way that “Westerners” today live whilst watching the effects of our Military Industrial Complex play out around the globe in real time. Art historians continuously search for evidence of ambivalence over this position in the many incredible painting works of the era, but are more likely to find Calvinist moralising over the possession of wealth or sugar than over the source of that wealth.[16] Reading of the conditions for the processing of sugar under the Dutch as well as the English, which could only be produced at great human cost, with hands regularly ripped from the arms of African slaves in the machinery, I was struck by the pointlessness of that trade, and felt quite glad that Queen Elizabeth I’s teeth rotted out of her head because of overconsumption of it. Another of the more particularly horrific examples of the actions of the VOC is the securing of the nutmeg trade in the Banda Islands, where 15,000 people were displaced/enslaved or killed, literally a genocide for the sake of monopolising a single spice, which was then only found in those islands. Shortly thereafter the technology was developed such that nutmeg could be grown anywhere. One respected historian Anthony Reid “squarely implicates the aggressive policies of Dutch commerce among “The Origins of Southeast Asian Poverty.”[17]

In the same year of the publication of the Liberum Mare at the behest of the VOC, the Amsterdam Exchange was also founded, which was to be the world’s first stock market,[18] made to manage the affairs of the VOC (founded in 1602)[19], the world’s first stock issuing company. The VOC’s innovation was to spread the risk of ships sinking, etc., across multiple investors (and foreign investment was encouraged), such that loss would be shared amongst shareholders and the profits from the wider fleet divided up. [20] During the same time period the English East India Company (EIC) was also operating, though it was not until the 1650s that it adopted such Dutch innovations as “transferable shares, a permanent capital, and limited liability for owners and managers” which economists Oscar Gelderblom (actual name)[21], Abe de Jong, and Joost Jonker attribute to a “lack of limited government”, in an article entitled “The Formative Years of the Modern Corporation…” [22] which I suppose means that corporations flourish when no one can be held legally or financially accountable.

Accounts from the period after 1608 reveal that internally the Dutch were annoyed that the EIC exploited the trade opened up by Dutch military operations “freeriding on Dutch power”, as the enormous cost incurred in securing supplies by force, basically from the beginning meant that the VOC essentially made little profit,[23] and little or no profit after 1650, which was largely obscured by convoluted accounting practices.[24] When finally the VOC folded in 1799, it was 120 million guilders in debt, which, if one extrapolates from Fisk’s sum (and my maths is correct) would be something like 12.2 trillion dollars in today’s money. And yet the shareholders were paid.[25]

AUSTERITY FOR ALL

In perhaps the first comprehensive work on the origins of objects placed in still life painting, Dutch Still Life and Trade, Professor of Early Modern Northern European Art Julie Berger Hochstrasser rigorously details the relationship between these paintings and the imports of the VOC, relating the trade to the interests of potential art buyers. In one particularly convincing aside, Hochstrasser advances the correlation between paintings containing wraps of pepper made by Pieter Claes and years in which pepper was trading at a particularly high price.[26] Hochstrasser also traces the evidence that the buyers of these paintings were very often involved with that particular speculative venture.[27] Pepper was the chief cargo of the VOC,[28] and though it may seem a relatively humble and quotidian substance to the contemporary viewer, in the 17th century it was a luxury good imported from Indonesia.

The contemporary view of the modern-day Netherlands as a prosperous nation belies the foundation of how business interests of the 17th century came into being. In some ways, the move towards trade by sea was inevitable as the Netherlands were reliant on trade for survival, unable even to grow enough food to support its population. Grain was called “the mother trade”, as it was a fundamental part of any Dutch diet but could not be grown within the Republic (and was mostly imported from the Balkans), to such an extent that it was not until more recently that historians came to reassess the bulk of VOC trade as being of “luxury goods”. Herring was a major export and yet even the salt needed for preservation had become impossible to produce, as the traditional practice of burning salt-rich earth lead to the flooding of the sea dikes, and was an altogether bad idea in land below sea level. The scarcity would seem to have encouraged a world view essentially envious of pleasure and abundance, one which might be said to carry through to our own understanding. This is echoed in Hochstrasser’s reference to the apparent surprise of Calvinist preacher Godfried Udemans at the bounty found in Indonesia among the “heathens” and his bizarre justifications for the plunder and exploitation of the VOC:

“Having just reveled in the profit trade could bring, he next reminds himself and his reader that the true God is not to be served with gold and silver as the papists are want to do. True, the temple of Solomon was also full of gold... but Paul had explained that it was a werldtsch heylighdom (worldly sanctuary) that would last only until such time as Christ would bring to the high priests a more perfect tabernacle, not made by hand.

Troubled by the contradiction that heathen lands should be so blessed with material riches, Udemans resolves this with the reassurance for all poor but pious Christians that their spiritual wealth is the true treasure. “We must be hardly moved by the blindness of the Indians,” writes Udemans, and do our best to keep them in the light of Christian salvation. There are several reasons for this, but the most interesting is a sort of reciprocal agreement Udemans fabricates between Indian riches and Dutch religion: because these Indians are so liberal in sharing of their material goods, such as silver and gold, diamonds, precious stones, pearls, spices, sugar, and so on, so we are then obliged to make our spiritual wealth available to them.” The construction of such a convenient myth in this singular economy allows Udemans to propose that the Dutch gift of spiritual “goods” somehow repays the “Heathens” for their earthly ones. The reasons go on, ranging towards the bizarre.”[29]

Udeman’s was also to quite simply write that “All pious men are free, and all godless men are slaves,”[30] to justify the slave trade. I guess why I am not an accelorationist is this understanding that scarcity breeds ruthlessness. It puts me in mind of the Vikings, whose proper names seemed to always refer to instruments of war, a people spending their lives battling the scarcity of the unrelenting cold, that strangely occupy so much of the pop cultural imagination, probably simply for being so exceptionally white. I once had a dream that Odin came to me as an itinerant trans person of my acquaintance and handed me their eye patch. I did some research the next day to find that the followers of Odin were generally warrior poets who would either die horribly in battle or become king, as an avowed republican I was unsurprised but dismayed by my apparent fate. I also discovered that in the original Norse, the description of Odin’s return from death, where he discovered runes, is described as a “gestation”, as patriarchal religions will tend to have some trouble with assimilating the miracle of childbirth. The odd parallel with the written word supplanting natural creation also got me thinking. Odin was also quite famous for practicing magics usually reserved for women. And now I really only want to see Odin played as non-binary, not that it would get me to a Marvel film (and only partially because they are on the BDS list). Big fan of the incredible arts and crafts of the Vikings, the Poetic Edda, etc. but the burning of the Anglo-Saxon monasteries and the thousands of books between the 9th and 11th centuries, is stupid and shit behaviour, though one can understand how they are so admired by the contemporary “right”. And do you know what was going on in the middle east at around the same time? The Islamic Golden Age. Whenever one looks to the origins of “civilisation” there tends to be some kind of surplus that enables greater leisure and therefore greater thought, from the floodplains of the Nile to the outrageous bounty of the Mediterranean. So, what can we say of this “civilisation” built on envy and suspicion of those bestowed natural gifts and generosity such that it has enacted punitive measures, where prosperity was necessarily dependent on theft?

PROTESTANT AESTHETICS

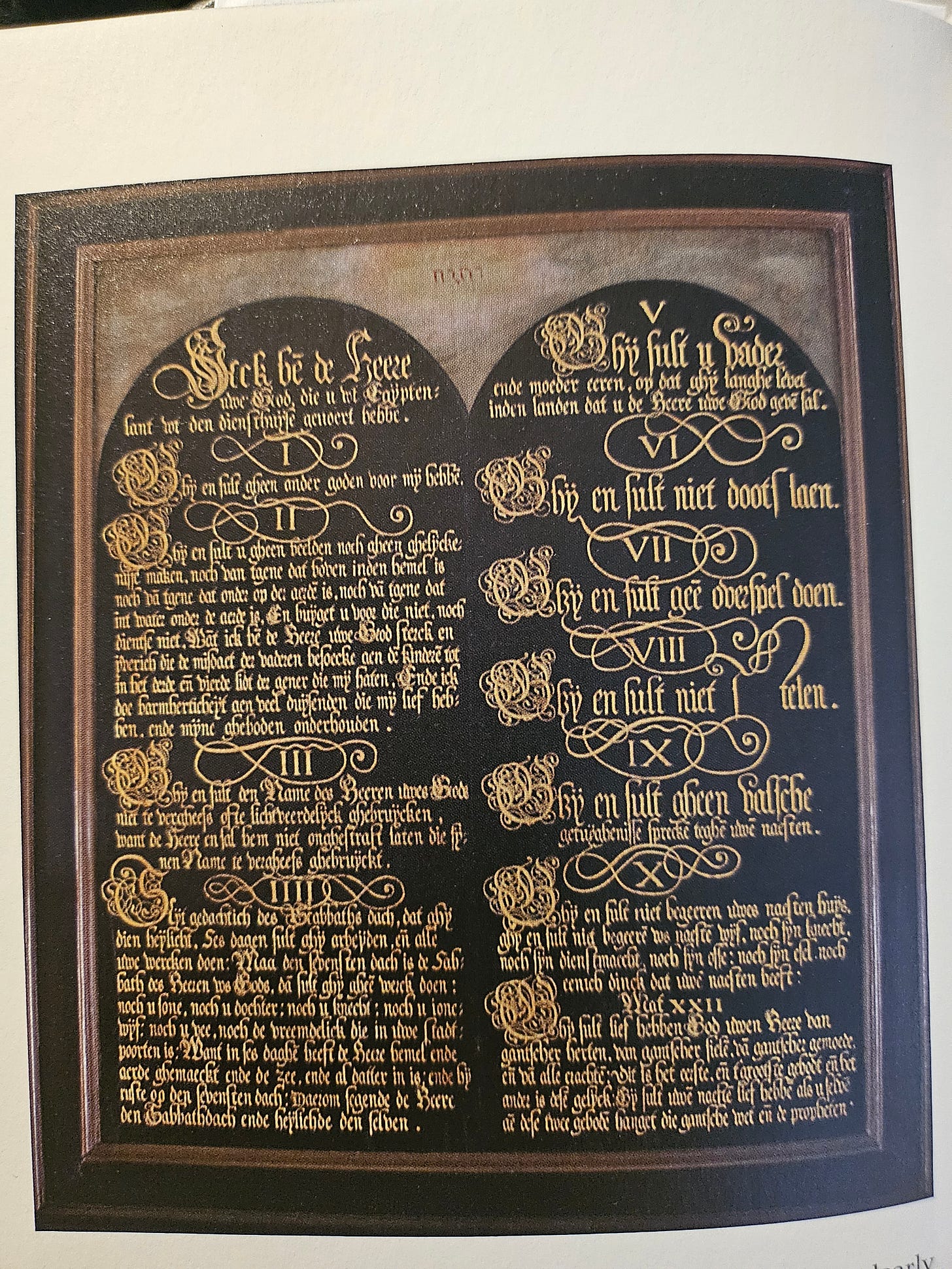

All Abrahamic religions, founded in the written word, take issue with the “graven image”. Though we may associate Protestant art most notably with the Vanitas movement, but with “realism” in general, the aniconism was in practise perhaps more fundamentalist than that of (later) Islamic aesthetic theology,[31] in that, at least in theory, it disallowed all illustration and decoration inside churches, effectively creating the “market” for secular art by casting artists from the temples. Calvinist churches would be have limited ornamentation and be white. White, at a similar time became the proper colour for both the heavens and flesh, as finally Europe came to grasp the value of “zero” in complex mathematics (based on the work of 8th century mathematician Al-Khwarizmi), for the sake of trade. Nonetheless, the extent of the minimalism of Dutch churches is sometimes overplayed, where the literal whitewashing was practiced for a couple of hundreds of years before the Reformation; and pulpits, for example, could also be innately carved… there was always some leniency in the theology for images that were unlikely to provoke false religious sentiment.[32] Hochstrasser explains that:

“Although Calvin rejected the worship of the Eucharistic bread and wine, he did endorse these visible signs offered to the eye to represent “invisible things.” In fact, contrary to popular opinion, neither did he condemn the visual “signs” of figural artwork outright: while he maintained that “all human attempts to give a visible shape to God are vanity and lies,” and thus that it was “not expedient that churches should contain representations of any kind, whether of events or human forms,” he also stated, “I am not, however, so superstitious as to think that all visible representations of every kind are unlawful.”[33]

Despite Calvin’s apparent ‘leniency’ in these matters, the effect of this imposition of whitewashed austerity was to leave artists without work.[34] As far as the churches go, new pictorial panels, encouraged by Calvin himself, came to adorn the altars, in the fanciest of early modern typography.[35] The particular biblical subjects were chosen expressly as a rejection of Catholic values, propaganda for the new religion bearing all the hallmarks of what we would understand as advertising. In The Netherlandish image after Iconoclasm Mia Mochizuki explains:

“In their pictorial language and choice of words text paintings indicate it was the doctrines of incarnation and transubstantiation that were under attack. The image debate was not simply a dispute on how to decorate a church, it addressed core values of the Catholic Church. And this goes a long way toward explaining why religious images fundamentally mattered so much in sixteenth-century Netherlandish society and why people staked their lives on this position.”[36]

Ten Commandments, 17th century. Harlingen, Great Church

I am just going to put this here…

But it is still the case that 17th century Dutch Calvinist churches, some forcibly reappropriated from Catholic worship and renovated accordingly, are strikingly austere. In the course of such renovations, artworks were ripped from churches (though often preserved for posterity), replaced with the written word. Wooden reliefs depicting biblical figures thought to inspire idolatry were often defaced, literally, where the slashing, especially to the eyes and face, strongly suggests the effort at making the figures unrecognisable. This is because, particularly statuary and relief works had come to form such an integral part of Catholic mass and processions that Reformers like Calvin believed the people to actually substitute the art for the real figure of Jesus, as such art works even came to include life-sized statuary with movable arms that could be interacted with. Calvin was in every way critical of material substitutes for spiritual subjects.[37] In Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (whose stated aim is to examine Still Life as an area of art that is largely ignored by the academy),[38] Norman Bryson writes of Calvin’s disdain for literal or materialist interpretations of the Bible:

“For Calvin, visualisation is the mark of a failed reading of the text: those who take literally the words depart from me... into everlasting fire, and proceed to visualise the fires of hell, are missing the inner meaning of the text: that the punishments of hell are terrible beyond sensual comprehension; fire is only a metaphorical representation. Ignatius would have the subject of devotion hear the roar, smell the brimstone, taste the tears, touch the flames. Calvin insists that the subject read the text; Understanding takes place not through visuality but rather through discourse in Calvins careful juxtaposition of text from Matthew and Isaiah. Calvin’s loyalty is to the word, not to the image, and so far from providing a direct connection between the subject and eschatological truth, the image of fire indicates only how such truth cannot be apprehended in terms of the body, experience or vision.”

The late medieval period had been awash with rather gruesome imagery to inspire both fear and devotion into the supplicant. Now that art was to be only secondary in places of worship it would take on a new role in this forcibly secularised society as a form of knowledge which tended towards a celebration of scientific development, a triumph mastery of craft and nature, often heavily symbolic, nothing to do with faith, belief or the unknown. Shells were a frequent theme, for example, for they encapsulated nature at its closest to human artistry. One need only look so far as the passion for the (polished mother-of-pearl) Nautilus cup, such as the one in the Kalf painting referenced above.[39] As eluded to by art historian Marsley Kehoe, these shells were also evidence of the anti-aristocratic turn in Dutch taste as these large shells were of no great value, found on an Indonesian island by the Portuguese, and favoured as an object of humble beauty before the establishment of the VOC, though, somewhat counterintuitively often presented in the finest of gold and silver metal work. They only turned up in Still Life paintings as the fortunes of the VOC faltered (around the 1650s). Gone were the palaces of the elite of the Catholic/feudal era, replaced with quaint bourgeoise opulence.

In a chapter “Forbidden fruit? Protestant aesthetics in seventeenth-century Dutch still life,” (in a book entitled Protestant Aesthetics and The Arts), Hochstrasser explains the effect of the turn against pictorial depictions of biblical scenes of the then new Protestant religions on those craftspeople traditionally employed by the church: “This was the major schism iconoclasm had wrought in the art world of the Dutch Republic: without ecclesiastical patronage, painters sold their wares generally at town fairs, giving rise to the overtly secular subjects of still life, landscape, and genre scenes of daily life, on the first art market in the Western world.”[40] Thus “secular” art is something that from its inception was central to the new Protestant order, operating in tandem with the very origins of capitalism. Bryson further explains that “The art market effectively appeared at the same time as the Stock Market and has always worked in direct service to the tastes of a speculative class”[41]. In fact, more prosaic readings of Protestant vs. Catholic themes within Dutch paintings of the era tend to prove the opposite of their intention. For example, take the understated and rather humble still life works of the Catholic Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz Heda, which despite the occasional wrap of pepper are more likely to feature proud homegrown staples such as Dutch beer and cheese. In “monochromes” by artists such as Claesz and Heda, the frugality of the Dutch household is emulated even to the extent of the choice of pigment, where such colours as blue, for example, were avoided as at the time they were produced through the expensive process of grinding semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli:

Pieter Claesz, “Still life with smoking equipment, herrings, a beer glass and a stone jug”, 1644.

against the “pronk” or luxury[42] still lifes (pronkstilleven) of Protestant Kalf:

Willem Kalf, “Pronk Still Life with Holbein Bowl, Nautilus Cup, Glass Goblet and Fruit Dish”, 1678

Kalf’s work is strangely enervating when compared even to work of similar execution and subject matter, something that remains mysterious seemingly even to those who write about it. But it appears that the reason for this might have something to do with the psychology of the era. Because the idea that this wealth was then appropriated by the Dutch people is very far from the truth. Karl Marx wrote about the Dutch Republic as the “Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist” in Capital Volume 1:

“The system of public credit, i.e., of national debts, whose origin we discover in Genoa and Venice as early as the Middle Ages, took possession of Europe generally during the manufacturing period. The colonial system with its maritime trade and commercial wars served as a forcing-house for it. Thus it first took root in Holland. National debts, i.e., the alienation of the state – whether despotic, constitutional or republican – marked with its stamp the capitalistic era. The only part of the so-called national wealth that actually enters into the collective possessions of modern peoples is their national debt. Hence, as a necessary consequence, the modern doctrine that a nation becomes the richer the more deeply it is in debt. Public credit becomes the credo of capital. And with the rise of national debt-making, want of faith in the national debt takes the place of the blasphemy against the Holy Ghost, which may not be forgiven.”[43]

Still, as recounted by Hochstrasser, the Dutch Republic, in marked contrast to somewhere like France of the time, actually invested in (the imported) grain to be distributed among the poor regardless of the cost, during what remained of the cycles of famine as a result of crop failure until the end of the early-modern period in Europe,[44] a situation, which of course, was a major cause of the French Revolution. While most of Europe would intermittently starve, causing a decline in productivity as well as birth rate that would have dire consequences for early modern economies, in the Dutch Republic everyone was fed. But at the same time, over the course of the hundred or so years of the “Golden Age” the Dutch population actually stagnated, which is perhaps the most illustrative metric for the effect on the common people. The stagnation and even decline of the population was a result of a sea trade that was supposed to have created untold wealth for the nation, and this was largely because so few would ultimately benefit from this new wealth. This meant that it was still easy enough to find young Dutch men (and the sailors were predominately Dutch) to work in service to the VOC under conditions that are said to have been only marginally better than those living under chattel slavery under the Dutch (who were quite proud of comparably “humanitarian” attitudes towards their chattel, meaning basically they pragmatically did their best to prolong their lives that they might continue to make money off them). The often-spoiled provisions on board VOC ships, along with disease, not to mention the many wars fought, meant that it was only 1 in 2 or perhaps even 1 in 3 young sailors that was to return from any given journey, accounting for the population stagnation. Kalf’s paintings on the surface triumphantly juxtapose treasures from throughout the globe that he bought and sold as an antique dealer, and yet they are unutterably dark. Hochstrasser writes that:

“If one was looking for psychic content here, then much closer to home, for example, was Kalf’s own experience: in January 1642, when Willem was only 23, his younger brother Govert died on board the Amsterdam on a trip to the East Indies. Perhaps Willem’s collections of treasures from the East – Chinese porcelain, Turkish carpets, Nautilus goblets, silently mourn this loss, now indeed “the very loss that haunts the subject”.”[45]

COUNTERREFORMATION

Protestant aesthetics were immensely various and often contradictory, they could be humble, austere, decadent, simple, complicated, brief and overworked; but they were always bourgeois and thus rarely unpleasant. It seems as though the counter-reformation was to provide the direct antidote, take the spectacular counter-reformist church at Santo Stefano Rotondo in which the means of the martyrdom of each saint is constructed in great detail.

Painting of Saint Artemius being crushed, in Santo Stefano Rotondo, Rome.

These are perhaps not subjects best optimised for selling for people’s interior décor, and so seem to mostly have fallen out of fashion in terms of a trajectory of European painting until the present moment, but similar themes have been lurking in the background ever since. (Notable counter-reformists of the 20th century might include Hermann Nitsch and Paul Thek, the weird Catholic antecedents of the restoration of medieval body horror.) In fact, there is something of a revival of counter-reformation aesthetics that seems to transcend allegiances both theological and political, a maximalism that we can only hope will undo both the international Airbnb style and normcore. The funny thing is that European aesthetics are so hopelessly mired in these theological preoccupations, and few have any idea of what these zombie forms actually mean due to a dearth of theological education. I mentioned a few blogs ago that this Northern versus Southern, Protestant versus Catholic aesthetic revival is sometimes playing out in luxury fashion, the Renaissance of Alessandro Michele’s Gucci against the Gothic of Demna’s Balenciaga, just selling the idea of Europe now that “the West” makes nothing but the idea of itself. But what I failed to elucidate is that both are a simultaneous embrasure and rejection of modernity, of a Protestant ethic, because both are versions of Catholicism, of Europe when ruled by the church and not the corporation. Luxury has it that certain consumers can afford to look other than neat and professional, but more than simply referencing the feudal, fashion is doing what it always does and borrowing from subcultures, from kids at art school thrifting. Take the typography inspired by lettering from before the printing presses sometimes called “cybersigilism”, in barely legible tattoos and emblazoned on upcycled fashion that seems to derive directly from memes.

Considering the famously Evangelical American conservative movements, the alleged neo-conservative move towards Catholic conversion does also bare some thinking about.

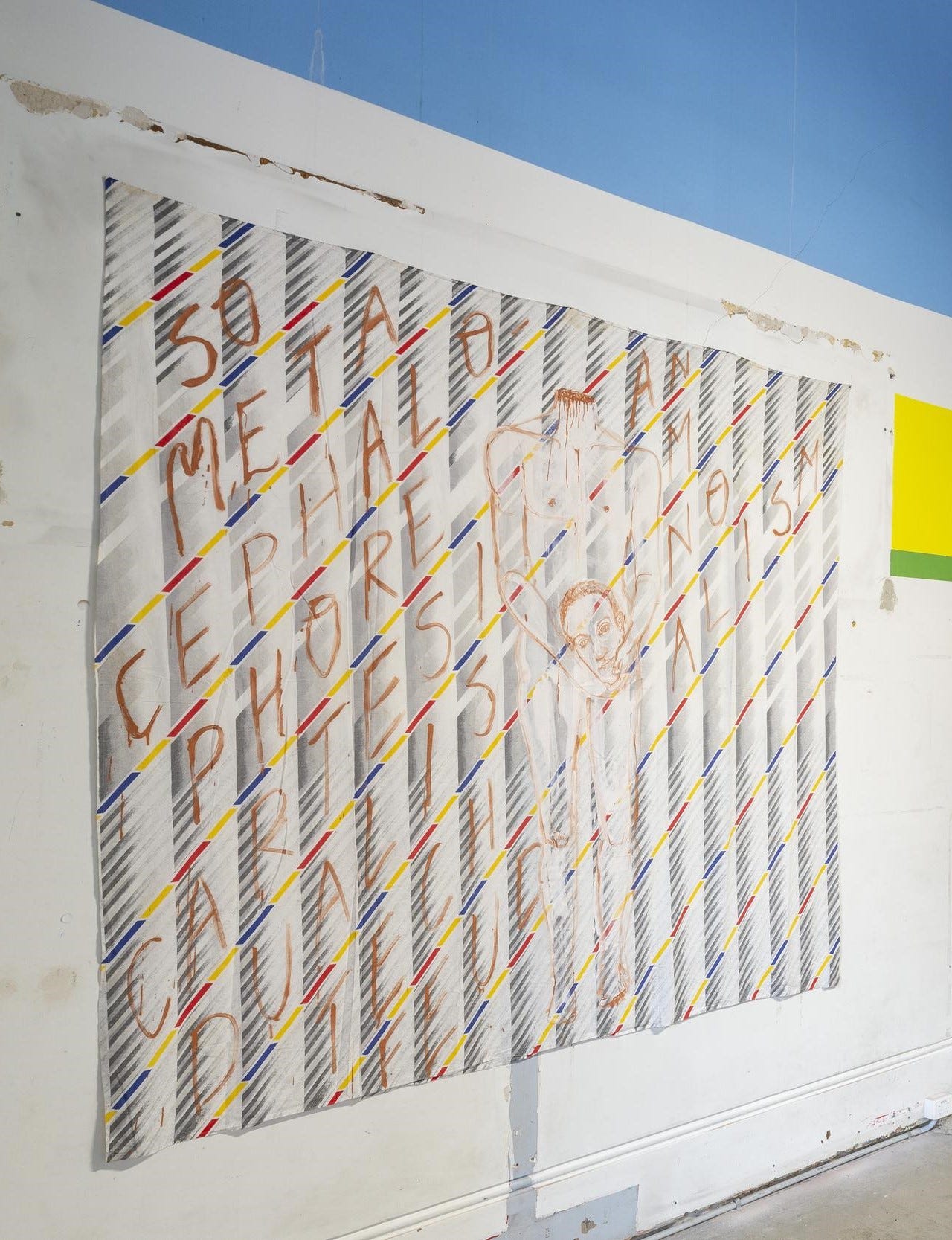

The right wing turn against “elites” may well make sense of this trend, where the famed WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) of the upper echelons of North American society are rejected (if only for other WASPs). The moralisms of our era, of representation over action, of the moral superiority claimed by warmongers, has its origins in the Reformation. Just as this marked Protestant resistance toward mundanity in religion, against any bodily representation may be said to underpin the aspirations of the current technocratic regime. Mochizuki further explains that: “Iconoclasm was always the story of the problems of bodies – human and divine bodies, living and inanimate bodies, governing bodies and the pushing and shoving bodies of the market square.”[46] Thus, counter-reformist aesthetics are a means of rejecting the false morality as well as the immaterialism imposed by the present. For, ironically, given the trajectory of Reformist thought, we are now supposed to believe that our representations are greater than our lived experience as though we have now created the world beyond the world that Calvin argued was the provenance only of religion. My painting of Mark Zuckerberg, for example, was both a joke about all the memes where people have found medieval monks that look just like him, as well as how he thinks putting a headset on will be as good as actually going to a concert.

"Technofeudalism I: Meta Cephalophore", MMXXII. lime wash on (soiled)(discarded) cotton (bedsheet). Approx 2100 X 2100mm.

One might argue that this stems from problems arising firstly from the rejection of visual and sensual experience as a realm of knowledge (both spiritual and intellectual) and secondly from the problems arising from the very strange notion that the written word is somehow separate to its very visual and mundane presence and somehow the arbiter of objective truth. Bryson explains the Calvinist discourse surrounding the written word in relation to 17th century Dutch painting:

“For Calvin the experience of devotion is necessarily aniconic; images get in the way of the contact between reading subject and sacred word. Vision is under suspicion; Figuration must be subdued and directed by figures of speech. Vanitas painting of the 17th century grows out of the deep internalisation of this priority of the word over image; Instead of word and image fusing the white heat of indigenous imagination, they are divided, the better the word may rule. As the branch of painting devoted to eschatalogical truth, the Vanitas accordingly installs the greatest possible distance between visibility and legibility.[47]

This prioritisation of course carries through to the University-lead art programs of today, wherein visual representation is codified as secondary. Whereas in other language systems, such as Arabic, calligraphy has always directed the viewer to the visual nature of the word quite apart from the objectivity with which we readers of the Latin alphabet have invested it.[48] Meanwhile, the aforementioned church altar typography, while often excellent, exists solely as a means of decorating the word, as though not to communicate anything but the importance of these disembodied ideas, which is another odd divorcement that makes Western thought so strange. We have a visual culture completely subordinate to ideas being communicated through text as though it does not exist in the world, our version of the “secular”, which, as we can see, is a result of a theological position not necessarily held by the majority of practitioners of Contemporary Art.

I am reminded of this when I walk again to Chinatown to Suite 7a to have a stained dress rescued, embroidered by Melbourne-based artist Safa El Samad (in the midst of her exhibition about distance, in part inspired by her estrangement from her Egyptian partner who was denied an Australian visa after graduating university here). El Samad offers a series of designs, references to Palestinian wildflowers and Arabic script. I choose a design in which a wildflower cuts through the Arabic word for “war” in such a way that leaves the Arabic word for “love,” as well as the Arabic for “free Palestine”. Concrete poetry as augmentation of otherwise doomed garments might not save the world, but it is a beautiful possibility for the future. The whole experience is lovely, watching the embroidery machine quickly manifest the designs and speaking over the whir with El Samad and the gallerist, former Greens politician and curator, Rafaela Pandolfini, as well as her partner Dom and one of their kids, and ceramicist Catherine Flora Murray who has wandered in early. It feels like a real community.

Vanitas paintings are today most closely mirrored in pseudo-political art, both that which is purely constituted “identity politics” and that which makes insane claims towards improving the world. These works present a shallow vision of morality as somehow completely divorced from its own material circumstance, utterly reliant on horrific exploitation. Circulating at the moment is an article “The Painted Protest: How politics destroyed contemporary art” by Dean Kissick, seemingly a hit with all the smart, cool younger men of my acquaintance… while sympathetic on the point of gleeful regarding the hypocrisy of “identity art” that has been championed in the institutions for years, I have quite a few issues with it. Because, the “political art” that Kissick so excoriates is really anything but. It is the same shallow, opportunistic bullshit that only white people were allowed to make 10 years ago.

Kissick’s article is so fantastically publishable because it claims all acts of conscience and solidarity are inherently polarising, where the underlying socio-political orthodoxy that is complicit in mass murder is somehow neutral, which is basically the problem with the “identity art” of the institutions. Like, I have no doubt that the exhibition at The Barbican described by Kissick was probably rubbish, and it is funny to laugh at artists who kept their work in an exhibition with a few silly “political” slogans attached to allude to the others that were boycotting (because of anti-genocide speakers being deplatformed). But to argue that Boycotting complicit cultural institutions is an overreaction fits very nicely into the liberal agenda. We are at a civilisational impasse in which it has become evident that most of the donors of major organisations seek to elicit the goodwill of these actions for the sake of the silencing of dissent (one need only look so far as the Sacklers). An older artist recently audibly scoffed when I mentioned a “moral compass”, and that is pretty illustrative of how such ideas were seen during the time that Kissick reifies, as though transgression was incompatible with a conscience. Nan Goldin has consistently and decisively proven otherwise. Kissick’s moral equivalency meanders through his hipster free-associations, heaping praise on some of the art of the day while being generally dissatisfied, choked with nostalgia enough to have forgotten that the art of our generation was every bit as hypocritical, shrill and impotent. But not for Kissick who writes:

“Only ten years ago, the art world was something very different: a globalized circuit of biennials and fairs that ran on the international trade of ideas and commodities. It was a space of spectacle and innovation, where artists tried out wildly different mediums and entertained radical ideas about what art could do and why. They were workshopping new cultural forms for a new millennium. Art was where experimentation happened, where people worked out what it felt like to be alive in this strange new century and how to give that feeling a form. Artists were researchers who were never expected to come to any conclusions. They had the freedom of absolute purposelessness.”[49]

Purposelessness, as long as one didn’t stray into the territory of articulating anything politically meaningful (like I have said repeatedly, this is not my first witch trial). And this is the substance of my argument – these missives that argue against all meaning and substance aren’t arguing for art so much as to turn the cash flow back on. I agree with Kissick that the best art is essentially idiosyncratic, as opposed to commissioned. But it is also very difficult to pin down Kissick’s alleged vision for what art is and can be, because doing “research” for the sake of art that he argues should be meaningless seems to be exactly what is going on right now (just try reading anything published from a university postgraduate program). And this is because while bemoaning liberal orthodoxy as though he is half-way to a break-through, his capacity to communicate is cut-off by this need to conform to the vision of all politics as a culture war and not vital acts of resistance, the aestheticisation of politics that became cool with the postmodernists, and fit so neatly within the neoliberal order. He is a plainly seductive writer hobbled by a lack of moral clarity, because back in our day, as now, moral clarity was/is very uncool. You can have it all back, Kissick, jet-setting with Hans Ulrich Obrist, “turning up to the club with your girl and five of her friends”, I will be pursuing better artistic ends in those divested from the capitalist nonsense that has been masquerading as art for far too long now.

AT SEA IN THE GIG ECONOMY, AWASH WITH SPUNKS

To return to Jacques Brel, for a moment, the life of the sea, and the misery of Dutch sailors, I have always been uncomfortable with the end of “Dans le Port d’Amsterdam”, which turns from the abjection of the sailors to the sex workers within their midst “Ils pissent comme je pleure – Sur les femmes infidèles” (and they piss while I cry – over the faithless women). It is certainly an anachronistic sentiment. Sex work is real work, Jacques. And yet to think on the circumstances he speaks to, there is something genuinely relatable in the most human of relationships being made to be utterly transactional. I am not alluding to sex work, which is very often an incredibly caring profession, but rather our parasocial lives lived out through social media, forced into attempting to survive via attention. In fact, I have recently seen a couple of articles about women seeking out male sex workers due to their disappointment over the way they are treated by men on dating apps. Their reasons for seeking such an arrangement are basically the same as what one would expect of men in the same situation, and yet men are not afforded the same compassion, even as it becomes more difficult for anyone to afford to have a family, for example. Thus, the parallels with those forced to spend their life at sea. Fucked if I don’t feel like I am living my life at sea a lot of the time. And Brel loved his wife his whole life, from whom his profession often separated him, she is everywhere in his music, from “La Chanson des vieux amants” (the song of old lovers) to his most famous work “Ne Me Quitte Pas”. In “Le Port D’Amsterdam” he is writing of those who are forced to disengage with what we contemporaneously understand as some of the most fundamentally human forms of experience, though, after all, not an extraordinary experience in the context of human history. In all the hysteria over loneliness, it is actually the expectation of a nuclear family unit that is the modern invention. And yet one can well imagine the horror such a romantic might experience at the idea of living without his love, as well as the transactional relationships of sailors. I suppose that at least among soldiers and sailors, and all of those forced away from home over years of their lives, one could at least expect camaraderie among one’s peers. Years spent away from loved ones is no longer a necessary condition for the majority, and yet loneliness is only the more increasingly distributed among the population, and there is little such camaraderie. This is no accident, the people are made to be increasingly distrustful of each other, which very much plays into the hands of those in power, this overwhelming breakdown in solidarity. I have now experienced, first hand, the exclusionary tactics I always suspected within my milieu, and the weirdest thing about it is how people I have never thought about have sought to punish me quite against their own interest, just in case it will make a billionaire class more sympathetic toward them. Meanwhile, I find myself surrounded with the most beautiful, intelligent, nurturing, incredible people I have ever known. Gestures of refusal are generally, in this way, immediately effective. It was obvious from the time that I began at art school that in this “industry” to “network” i.e. to treat relationships as transactional, is something that is socialised. All leisure time is taken over in service to projecting the right image, to try and be among the enfranchised few. The arts are nothing if not an industry built on desire and youth sacrifice.

Nonetheless, I have been in a cycle of moderate regret over my habit of mocking artists who attempt to sell their work, or perhaps just connect to other people, via “sex” on social media. I don’t know whether it’s some bizarre epigenetic throwback to my Irish Catholic (separatist) ancestors or what, but I really need to keep my piousness in check. Like, what, do I not want to look at scantily clad men now? Please keep taking your shirts off in front of your paintings, after all, you may find yourself immortalised in one of mine. (Mocking and lusting over men is one of my favourite pastimes.) (And definitely something I should keep to myself.) (I apologise particularly to any younger people reading this.) I don’t think I will ever shake this feeling that playing to the platforms is sullying, but fucked if we aren’t all implicated. As much as I insist on sporadic 10,000 word blog posts to alienate all potential audience, like some arcane renegade, I am not above courting controversy, which does tend to boost my readership. In many ways, it would be much more ethical if I just got my tits out.

WETNESS

Guild systems once provided a union and solidarity among those practitioners of the visual arts, whereas now that has all become decisively undone, if you are not doing well than it is supposed to be through your fault, and yet there are endless stories about those artists who were overlooked. When subject matter became liberated from religious concerns, it became centrally important to the work of artists, and very much the difference between starving and being a darling of patrons. While Kalf was very successful during his lifetime, artists such as Abraham van Beijeren, lived lives of penury. Van Beijeren was only to be “singled out” long after his death, in this case by twentieth-century scholars, as one of the most important Dutch still life painters of the period.[50] For, apparently regardless of its importance as a one of the trade goods produced in the Dutch Republic, fish was not to be one of the more popular subjects of still life painting, or at least the many vivid and mildly gory fish paintings of van Beijeren. Other painters took on fish as subject matter, of course, and lobster and oysters were a common theme even of Pronkstilleven, such as those by Kalf but also Jan de Heem, Willem van Aelst etc.. But other painters of more humble fish such as Claesz and Claesz Heda also assumed the perspective of the consumer. Bryson writes of the conception of labour in Dutch still Life as something quite independent of earlier still life works, where in Ancient Greece or Rome, these works might have been seen to allude to xenia/philoxenia, “hospitality” and “hospitality towards strangers”. depictions of abundance as provided amply by nature. But it is evident that the Dutch had a very different experience of nature, which required hard labour and organisation to attain anything like the mastery necessary for base survival. Bryson thereby describes Dutch Still Life as “georgic” rather than “pastoral”. He also makes the point that quite the opposite of flower paintings from, for example, Pompeii, which present flowers freshly cut from local natives in pastoral scenes, Dutch flower painting is “georgic” in its display of flowers that have been brought back from all over the world, monuments to enterprise over the base enjoyment of simple nature. The very fastidiousness of the paintings of the era allude to the importance and value placed on labour above all else, certain painters were even paid for their time, and yet, of course, many don’t seem to have been paid much at all.

Suffice to say that in selling to an open market place the remuneration of painters, even of those painting still life, was far from uniform, which has proven to have little or nothing to do with skill, which one might argue, has come to be accepted as objective truth within this system to the point of romanticisation. Nonetheless, it is something hard to imagine under any other kind of system, where contributing to the decoration of major cathedrals, for example, a skilled painter might almost be guaranteed work (though, of course, Caravaggio’s many trespasses against the dignity of his religious subject were quite often rejected by his patrons). When artists who had traditionally worked in religious subject matter especially in churches were forced to ply their trade on an open market, paintings became relatively affordable and widely owned. Hochstrasser contends that there was likely a close association between those employed in the fishing trade and Van Beijeren, who would have had more class interests in common with fishmongers and fisherman than those he made his apparently unsuccessful attempts at pronkstilleven for (she points to a commission Van Beijeren received from the fisherman’s guild).[51] Where van Beijeren is basically unique as a painter is in the literal and metaphoric rawness of the fish, the relationship between the fisherman and the yield, the intimacy of the scenes with fishmongers. Take this painting of a fishwife who looks to be in her 40s, her finger hooked through a suggestively-shaped opening in the pink flesh of a fillet of fish, her glistening wet wares laid out bare before her as she stares intimately into the viewers eyes, the sea and fisherman visible through the window behind her:[52]

Abraham Van Beijeren, “The Fishmonger”, 1666. Tempera on canvas, 121 x 146 cm

One can only imagine, in the days before refrigeration, how smelly and wet was this scene. The term “fishwife”, at least in English, would of course connote a supreme vulgarity, but this painting sort of makes me want to reclaim it. It is unusual to see such a painting, weighted as it is in an equality of the subject, where the fishwife returns Van Beijeren’s gaze without pretense or coquetry, a handsome older woman at work, neither amused nor embarrassed by the nakedness of the seductive gesture. As I have written about in relation to the work of Lucas Cranach, both the elder and younger, it was the Reformation that ushered in an era in which the sexuality of older women was rendered absurd as sex was reduced to pure reproductive form. Cranach’s nudes were simultaneously propaganda for the Reformation and erotica, as much as that seems counterintuitive. The roots of our very understanding of women as mere vessels for the productivism of the new religion was enshrined via early Protestantism (which is not to say that the Catholics have a better track record on women’s reproductive health). Thus, all these genocide-adjacent public feminists who evoke motherhood as a sacred value, with all of the resources at their disposal, while arguing for fundamental inequality are a function rather than an outlier in the continuum. So, like much of Van Beijeren’s work this painting feels oddly anomalous.

TACIT CUNTS

Cunts. Why are we so afraid of them? In the early modern period they appear all the time, quite fabulously in depictions of Christ’s side-wound, [53]

…to an extent that might have made the Marquis de Sade blush (he was said to actually have been horrified by Santo Stefano Rotondo). There are also many images from the medieval period of women exposing their genitals to devils to scare them away (mad cunts). I can only conclude that in this age of devils, these symbols are buried such as to stop them from getting a fright. As a total cunt I offer you protection. (In case anyone has strayed in from an extra-antipodean context there is nuance to the use of the word cunt here, where sick cunt and mad cunt represent the best one can be and dumb cunt and shit cunt, not so much. Cunt on its own is more-or-less universally understood.) Jesus, like Odin rose again, which more than cheating death seems like a way to cheat birth (which is plainly heretical). But I do not mean to diminish either figure, I am actually a huge fan of the teachings of Jesus, a Palestinian socialist, and ambivalent about my calling as warrior poet (though fascinated by the ingenuity of the Viking era). But patriarchal religions find a way to repress the miracle of childbirth until shit gets weird. What is strange is that while young men draw penises on everything, yoni symbols seem to have fallen utterly out of favour. Nowhere is this more literal than in the work of Justene Williams, whose branded monumental figurines are called “Sheila”, like a fun pun on “Aussies” but also like the predominately Irish Celtic totems known as Sheela na gig. The only defining feature of the Sheela na Gig, i.e. a monstrously enlarged vulva, is nowhere to be seen (William’s mentions the need to tone it down for the public, but has produced basically the same structure before, also without obvious vulvic associations).

Sheela na Gig (12th century?)

Justene Williams. “She has no beginning or end”, 2022 installation view, Sarah Cottier Gallery. (“Sheela” pictured on far right.)

As best we know, Sheela na gig offered warm, womb-like protection and/or fertility, carved above doorways, with all the associations of openings. Williams’ innovation seems to have been to make her legs the opening, thus monumentalising her while censoring her. It is the equivalent of a sculpture of Priapus without a penis (but with big arm muscles, as Williams’ makes much of “Sheila”’s large breasts). I was never particularly interested in Williams’ work, but to look at the fun, cheap materials and bright colours in the well-documented commercial exhibitions now almost makes me nostalgic. When I first saw the exhibition above, as a long-term fan of Sheela na gig, I felt mildly irritated by the poorly executed, crude carving. I felt that it was perhaps even patronising to the pre modern sophistication of the carvings, as much as the shying away from any representation of female genitalia. But the translation between fun polystyrene works to the much more “luxe” material of bronze, which seems to be an inevitable move for anyone wanting to be a “serious artist” in this country, is basically unkind to Williams’ practice:

Justine Williams, “Sheila”, 2024.

Williams’ “Sheila” might be described as a literal dumb cunt for lacking one to speak to, or better through. In the lead-up to the unveiling of this monumental sculpture in Brisbane, Williams explained that she wanted to make a female superhero for her daughter. She also describes the work as being about “body positivity”. The superhero intention is a bit gross, a product of an art world aiming to mirror the monopolies from which it can only hope to draw its funds… but I have no doubt that Williams meant it such that her daughter should have a better life and be able to achieve anything without the discrimination against women that is still prevalent. Moves towards “body positivity” are surely admirable. But the trouble with these feminist figureheads in reply to patriarchy is that they so often prove disappointing both as totems and in person. I remember seeing Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek speak during my undergraduate degree and being quite motivated to vote for her. The Albanese Labor Government she is a minister for, was elected with a mandate to do something about Climate Change, in a country that now seems to alternate between devastating floods and bushfires, and Plibersek has responded by expanding the coal industry, even approving three coalmine expansions in a single day this September.[54] This can no longer be seen as economic pragmatism as the world divests from fossil fuels. These failures are literally killing thousands or hundreds of thousands of people. Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong, and American Vice President Kamala Harris have both overseen genocide in Gaza, doing little or nothing to mitigate the killings by a close ally, even providing resources to continue. Margaret Thatcher is dead… best thing I have to say about the woman. Personally I prefer representative over representational democracy, and yet I don’t think that any of us have ever seen what that looks like. Williams’ had a pop up exhibition at a Melbourne gallery that had recently made headlines by censoring and parting ways with one of its artists over Palestine… I am reminded by a mutual friend that artists are often politically illiterate. I just believe that such an illiteracy is something of an oversight in a praxis, where the better artists of the modern era have tended to understand their impact on the society and manipulated it (I had a whole section on Rembrandt Van Rijn that will have to wait for another blog). And regardless of good or ill intention, for me, “Shiela” will always stand as a suitably facile monument to corporate, genocide-adjacent feminism.

The imperative toward “public art” which is really only monumentalism, in Australian art of the moment, is consecrated by an ideology that pretends not to be, a regime that claims innocence while entrenching poverty both globally and locally. It is even signaled as a virtue that massive new developments are legislated as to have to have “public art” accessories attached, because art is apparently an inherent good. It is here where an artist proves their worth via tender, being chosen to uphold the ideals of this society by creating a monolith in the name of the public, with hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars of public funds, in the midst of such crises as housing, groceries, genocide here and abroad, climate catastrophe and all the rest of it, and I can’t help but find it utterly morbid.

Mike Hewson, “St Peters Fences”, 2020. A playground made with fences of the houses destroyed to make room for major tollway “Wesconnex” (with Wesconnex money).

I do not want to go down the rabbit hole of the current “Australian” mania for playgrounds, but I do think that I should reference the works that may have started the whole thing, thank you very much again, Mike Hewson, because I do actually like his work. Playgrounds are generally depressingly mass-produced, and seem like a reasonable thing to devote resources to improving, though these things always seem to end up with a bunch of opportunistic artists trying to make it their practise as well. Perhaps I am over-prone to psychological readings of artworks, but I can’t help but see in Hewson’s playgrounds the fecklessness of the millennial alpha male, priced out of the baby market and spoiled for choice with so many women on offer via so many platforms and venues. The choice to express himself by trying to build a better world for other people’s children, in the richest part of the pipeline of the cross-city tunnel, strikes me as deeply neurotic and oddly mournful. And so we are left with the basest economic circumstance, fundamental alienation that is a feature of the system that needs to split us apart to keep us polite. It is very rare for public art to provoke feelings of such a personal nature, thus meeting the criteria for actual art. It will be interesting to see if Hewson’s work shifts now that he has settled down… It was always as though he was coming to terms with his own Peter Pan complex (she writes while wearing a Dinosaur cardigan). Obviously, my assessment should be taken with a grain of hard-earned Dutch salt, as I am very clearly projecting onto Hewson’s handsome visage.

Of course, I cannot help but mention Lindy Lee’s latest unveiling at the National Gallery in Canberra, “Ouroboros” which cost $14 million AUD. I have no problem with Lee or her work, and was actually happy to hear she got the commission after the last incredibly expensive ‘captains’ pick’ for that gallery was the embarrassingly bad and meaningless work of American artist Jordan Wolfson, which we were able to secure for a cheeky $6.67 million AUD (someone told me last night that it is also an edition).[55] It is as though gallery director Nick Mitzevich in paying astronomical prices for artworks, sees himself as reliving the glory days of the gallery when it was first founded by deposed Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and its first director, who, in a great irony of history purchased CIA darling Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles for $1.3 million AUD, then an extraordinary sum.[56] Of course, it is an important piece of art history now apparently “worth” $500 million. The Whitlam administration did many things to annoy the Americans, universal free healthcare and tertiary education, indigenous land rights, the list goes on. But it seems as though they were ultimately victims of the machinations of the CIA and MI6 for trying to get American army bases off of Australian soil. I very much doubt the return on investment of the Wolfson work or this rather derivative work of Lee’s. A gushing article in the guardian mentions that it was so difficult to engineer that they had to send for someone that worked on Anish Kapoor’s “Cloudgate”, which says it all, really. It is a cross between that Kapoor work and the perforations of Daniel Boyd. It is a pretty indifferent object, hardly different from one of the more underwhelming metal lobby sculptures in Finance buildings. It is also badly finished, with visible welding seams on the inside.

Like Williams’ Sheelas, it also has nothing to do with the ancient sacred symbol it claims to represent, and doesn’t even look like it. It is a commission whose sole value seems to be in how very expensive it is, that is probably befitting the vassal state of an Empire that is currently imploding. This is quite spectacularly topped off with the $10million solid gold replica “Abundance” owned by NGA sponsor, precious metals group Pallion (who were recently embroiled in a lengthy court case involving GST fraud).

But, as I continue to uselessly demand of public institutions to the extent of further burying my career, I would like to add, Ahlip’s entire exhibition at Schmick would cost the NGA less than $10,000, such that they could purchase 1400 exhibitions of that calibre for the same price as Lee’s work. While I feel Ahlip is underrated, he has just accepted a residency at the Gertrude Studios in Melbourne, and thus is hardly an unknown. I just don’t believe that “Ouroboros” is 1400 times better. Again, no issue with Lee, she was fulfilling a brief, and these artists are no worse than anyone else and their motivations completely understandable, brand building is basically the only means to base survival. But it is hard to see how these apparently secular works are really so different to the other monuments to Imperialism, the bronze statues of Captain Cook that still unaccountably dot the country. Every time some ludicrous sum is listed for some big thing is listed I wonder if it would have been enough money to buy back Juukan Gorge from Rio Tinto before they destroyed an essential piece of world history. This is a false equivalency, but it is just another example of why I don’t think that we, as a culture, have a whole lot to be celebrating. And the work is often just bad, even from artists that I think are incredible. I went looking for a terrible proposal from the otherwise brilliant Hany Armanious to build a giant milk crate, so widely panned that it was scrapped… and came across the one work of that funding round that the City of Sydney actually managed to produce, the bronze sparrows made by card carrying Tory (and Young British Artist or YBA) Tracey Emin, in a park nearby the Customs House Library where I write, which emulate a first year sculpture assignment in both concept and execution. But just as long as the art is expensive…

Tacita Dean, “Lord Byron Died”, 2003.

On the other hand, back to YBA Tacita Dean’s “Lord Byron Dies”, where ancient monuments are defaced by British tourists, of the grand touring age of the 19th century, which it seems all of Europe has been reduced to (of course, some of the writing is also in Greek). The beautiful copperplate gothic of the 19th century graffiti alludes to better times in the Empire. Dean said of the work:

"Some years ago, I went to Sounion in Greece to look for Lord Byron's signature, famously carved into one of the columns in the temple there. I couldn't find it. Instead, I photographed these other names, carved into the marble in the copperplate writing style of the vandals of that time. They are evidence of an era of Romantic wanderings, sea voyages and a new affinity with the Classical Age. Somehow it seems fitting that those carved works and numbers should now read as end dates for such a period of incomparable literary brilliance."